Siege of Dunkirk (1793)

The decision to besiege Dunkirk was taken not by military commanders, but by the British government, chiefly by William Pitt's closest advisor, Secretary of State for War Henry Dundas.

As a military objective towards winning the war, however, it was likely a mistake, as it prevented Prince Frederick, Duke of York from supporting the main Allied thrust further inland, and losing the strategic initiative.

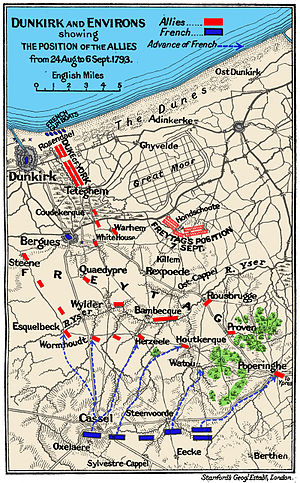

On 22 August he marched from Veurne (Furnes) to attack Dunkirk with 20,000 British, Austrians and Hessians troops, driving the French advance posts in confusion from the left bank of the Yser River to an entrenched camp at Ghyvelde, capturing 11 guns in the process.

[3] To protect York's left flank Heinrich Wilhelm von Freytag commanded a corps of 14,500 Hessian and Hanoverian troops which he spread across surrounding villages in a broad military cordon along the Yser to the south of Dunkirk.

[5] Meanwhile, in Paris the election of Lazare Carnot and Pierre Louis Prieur to the Committee of Public Safety was to have immediately beneficial consequences for the Republican field armies.

[8] York reported, "Unfortunately the ardour and gallantry of the troops carried them too far in spite of a peremptory order from me, three times repeated, they pursued the enemy upon the glacis of the place when we had the misfortune to lose many very brave and reliable men by the grapeshot from the town."

[13] Equally worrying for York was the news of a further check on the Dutch forces of the Prince of Orange near Menin on the 28th, which widened the gap between his command and that of the main Austrian Army further south.

Souham had opened the town sluices, which slowly inundated the fields connecting York to Freytag and filled British trenches on the dunes with two feet of water.

This assault was beaten back after intense close-quarter fighting and very considerable loss on both sides, Powell records the 14th Foot had 9 out of 11 officers injured and 253 men killed and wounded.

With news of his left flank exposed the Duke of York gave orders for his heavy baggage to be withdrawn to Veurne (Furnes), then at a Council of War on the 8th it was decided to lift the siege of Dunkirk.

[citation needed] Alfred Burne devotes several pages assessing the siege of Dunkirk and Hondschoote, including much of the Duke of York's subsequent correspondence to the King.

If the gun-boats and floating batteries had been ready, according to the express promise to co-operate with the Duke of York, and if his alacrity had been at all seconded on the part of the officers in England there is no doubt that Dunkirk would have fallen at the first attack.

[21] Burne also points out the oft-overlooked fact that the French broke the terms of capitulation at Valenciennes, which dictated that released prisoners were not to fight again, and sent repatriated prisoners-of-war straight to reinforce the garrison of Dunkirk.