Siege of Oxford (1142)

Fought between his nephew, Stephen of Blois, and his daughter, the Empress Matilda (or Maud),[note 1] who had recently been expelled from her base in Westminster and chosen the City of Oxford as her new headquarters.

It was a well-defended city with both rivers and walls protecting it, and was also strategically important as it was at a crossroads between the north, south-east and west of England, and also not far from London.

By now the civil war was at its height, yet neither party was able to get an edge on the other: both had suffered swings of fate in the last few years which had alternately put them ahead, and then behind, their rival.

Having raised a large army in the north, he returned south and attacked Wareham in Dorset; this port town was important to Matilda's Angevin party as it provided one of the few direct links to the continent that they controlled.

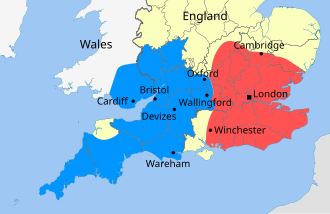

He attacked and captured more towns as he returned to the Thames Valley, and soon the only significant base Matilda had outside of the south-west—apart from Oxford itself—was at Wallingford Castle, held by her close supporter Brian Fitz Count.

One early December evening Matilda crept out of a postern door in the wall—or, more romantically, possibly shinned down on a rope out of St George's Tower—dressed in white as camouflage against the snow and passed without capture through Stephen's lines.

She escaped to Wallingford and then to Abingdon, where she was safe; Oxford Castle surrendered to Stephen the following day, and the war continued punctuated by a series of sieges for the next 11 years.

[27] The Empress Matilda—"in great state", reported James Dixon Mackenzie[28]—evacuated to Oxford in 1141,[29][note 3] making it her headquarters and setting up her Mint.

[31][note 4] Prior to her eviction from Westminster, she had made some political gains, having captured King Stephen and been recognised as "the Lady of the English".

[44]Although the size of the army Matilda took with her to Oxford is unknown, it contained only a few barons[45] with whom she could keep a "small court",[38] and for whom she could provide from the local lands of the royal demesne.

[51] Stephen had recently been so ill that it was feared, temporarily, that he was dying; this created a degree of popular sympathy for him, which had already welled up following his release from Matilda's captivity the previous November.

[note 7] A. L. Poole described the train of events thus: At the Christmas [1141] festival, celebrated at Canterbury, Stephen submitted to a second coronation, or at least wore his crown, as a token that he once again ruled over England.

The affairs of the kingdom, a visit to York, and an illness, so serious that it was rumoured that he was dying, prevented the king from taking steps to complete the overthrow of his rival who remained unmolested at Oxford.

[26] John Appleby, too, has suggested that much of her support had by now decided that, in his words, they had "bet on the wrong horse", particularly as she had failed to put up a stand at Westminster or immediately return in force.

[61] Stephen, on the other hand, had recuperated in the north of England; he had a solid base of support there and was able to raise a large army[62]—possibly over 1,000 knights—before returning south.

[66] This won him the port town of Wareham[50]—cutting the Angevins' line of communication with their continental heartlands[55][note 10]—and Cirencester, as well as the castles of Rampton and Bampton.

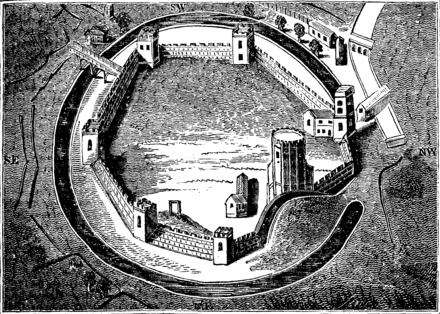

[70] David Crouch comments that the King "had chosen his time well":[72] the city's and castle's previous castellan, Robert d'Oilly had died a fortnight earlier[72] and his successor had yet to be appointed.

Stephen's primary objective in besieging Oxford was the capture of the Empress rather than the city or castle itself,[78][note 14] reported the chronicler John of Gloucester.

[73] Another, William of Malmsbury, suggests that Stephen believed that capturing Matilda would end the civil war in one fell stroke,[74] and the Gesta declares that "the hope of no advantage, the fear of no loss" would distract the King.

He prevented the besieged from foraging by pillaging the surrounding area himself, and showed a certain ingenuity in his varied use of technology, including belfries, battering rams and mangonels.

[85][note 17] These kept the castle under suppressing fire,[73] and it is possible that these mounds, being so close together, were more like a motte-and-bailey structure on the edge of the city, rather than two discrete siege works.

Anjou had refused to leave Normandy or make any attempt to rescue his wife; perhaps, says Cronne, "it was just as well he did, for the English barons would certainly have regarded him as an unwelcome intruder".

[73][note 21] After three months' siege, supplies and provisions within Oxford Castle had become dangerously low,[89] and, suggests Castor, "trapped inside a burned and blackened city, Matilda and her small garrison were cold, starving and almost bereft of hope.

The contemporary chronicler of the Gesta Stephani—who was highly partisan to Stephen[note 24]—wrote how:[75]I have never read of another woman so luckily rescued from so many mortal foes and from the threat of dangers so great: the truth being that she went from the castle of Arundel uninjured through the midst of her enemies; she escaped unscathed from the midst of the Londoners when they were assailing her, and her only, in mighty wrath; then stole away alone, in wondrous fashion, from the rout of Winchester, when almost all her men were cut off; and then, when she left besieged Oxford, she came away safe and sound?

They suggested that she had climbed down a rope out of her window (but, says King, "this was the manner of St Paul's escape from his enemies at Damascus"),[99] that she had walked on water to cross Castle Mill Stream ("but this sounds more like the Israelites crossing the Red Sea than the traversing of an established thoroughfare",[99] and the Thames[85] may well have been frozen), according to Henry of Huntingdon, wrapped in a white shawl as camouflage against the snow.

[55] Matilda's escape was, in itself, not a victory[106]—if anything, says King, it highlighted the fragility of her position[108]—and by the end of the year, the Angevin cause was, in Crouch's words, "on the ropes"[73] and what remained of its army demoralised.

This, he says, is evidenced by the fact that even though the Earl of Gloucester had returned from Normandy in late October, it took him until December to re-establish himself in his Dorsetshire heartlands,[73][note 26] as he wanted to reassert his control over the whole Dorset coast.

[109] Wallingford was now the sole Angevin possession outside of the West Country;[55] Stephen, however—although waging what Barlow has described as a "brilliant tactical campaign, distinguished by personal bravery"[66]—had also lost the momentum he had built up since his release from captivity, and had missed his last chance to end the war decisively, as he had planned, with Matilda's capture.

[115] The King is known to have attended a legatine council meeting in London in spring the following year, and around the same time returned to Oxford to consolidate his authority in the region.