Siege of Shaizar

Having been repulsed from their main objective, the city of Aleppo, the combined Christian armies took a number of fortified settlements by assault and finally besieged Shaizar, the capital of the Munqidhite Emirate.

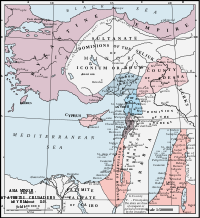

Freed from immediate external threats in the Balkans or in Anatolia, having defeated the Hungarians in 1129, and having forced the Anatolian Turks on the defensive by a series of campaigns from 1130 to 1135, the Byzantine emperor John II Komnenos (r. 1118–1143) could direct his attention to the Levant, where he sought to reinforce Byzantium's claims to suzerainty over the Crusader States and to assert his rights and authority over Antioch.

Faced with the approach of the formidable Byzantine army, Raymond of Poitiers, prince of Antioch, and Joscelin II, count of Edessa, hastened to acknowledge the Emperor's overlordship.

The Emperor then moved the army southward taking the fortresses of Athareb, Maarat al-Numan, and Kafartab by assault, with the ultimate goal of capturing the city of Shaizar.

[12] Following some initial skirmishes, John II organised his army into three divisions based on the nationalities of his soldiery: Macedonians (native Byzantines); 'Kelts' (meaning Normans and other Franks); and Pechenegs (Turkic steppe nomads).

[13][14] Although John fought hard for the Christian cause during the campaign in Syria, his allies Raymond of Poitiers and Joscelin of Edessa remained in their camp playing dice and feasting instead of helping to press the siege.

The Emir's nephew, the poet, writer and diplomat Usama ibn Munqidh, recorded the devastation wreaked by the Byzantine artillery, which could smash a whole house with a single missile.

Also offered was a table studded with jewels and an impressive carved cross said to have been made for Constantine the Great, which had been captured from Romanos IV Diogenes by the Seljuk Turks at the Battle of Manzikert.

However, Raymond and Joscelin conspired to delay the promised handover of Antioch's citadel to the Emperor, and stirred up popular unrest in the city directed at John and the local Greek community.

However, when Byzantine military might was directly manifested in the region, their own self-interest and continued political independence was of greater importance to them than any possible advantage that might be gained for the Christian cause in the Levant by co-operation with the Emperor.

[24][25][26] According to Niketas Choniates's early 13th-century history, John II returned to Syria in 1142 intending to forcibly take Antioch and impose direct Byzantine rule, expecting the local Syrian and Armenian Christian population to defect in support of this campaign.

His son and successor, Manuel I (r. 1143–1180), took his father's army back to Constantinople to secure his authority, and the opportunity for the Byzantines to conquer Antioch outright was lost.