Signal instrument

[3]Before the introduction of modern technological communication, signaling over a distance was often a very good way to pass messages, especially in difficult terrain such as the mountains (e.g. Alpine horn, equivalents are still used in parts of the Himalaya) or sparsely populated plains or forests (the tam-tam type of drums as with American Indians and jungle drums), sometimes using rather elaborate code systems to pass even complex information.

Another ancient function, which has survived into modern urban life is to assemble or warn a whole population or congregation at large, usually not coded or just for a few common cases, as with a conch or bells in a church or belfry: a variation for more local use is the gong.

Naturally then instruments are preferred which are not too delicate to be moved, and often not too heavy (except when the musician is mounted or in a vehicle) to transport, or even better be played during march or even chase.

When the social elite practiced hunting as a prestigious outdoors social activity, music was often present at any stage, e.g. the court of Versailles had composers such as the Danican family and Philidor write special symphonies for a court orchestra to accompany the royal hunt party, prominently featuring percussion and winds but also including non-signal instruments, even strings.

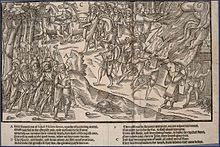

In the (para)military and similar, mainly uniformed, corps such as police, the tradition of march music stems from the use of signal instruments, mainly metal winds (as the modern bugle and clarion[1]), originally (and still) to pass standardized orders (often at a small tactical level), while percussion and flutes served mainly to march on the beat; especially when a larger force is gathered with ceremony (just drums often do, as in ruffles and flourishes or accompanying formal administration of corporal punishment), both can be combined into a band.