Silat

Regional dialect names include penca (West Java), dika or padik (Thailand), silek (the Minangkabau pronunciation of silat), main-po or maen po (in the lower speech of Sundanese), and gayong or gayung (used in parts of Malaysia and Sumatra).

The fact that this legend attributes silat to a woman reflects the prominence of women in traditional Southeast society, as can still be seen in the matriarchal adat perpatih customs of West Sumatra.

This story is often told in the Malay Peninsula either as the origin of a particular lineage or to explain the spread of silat from the Minangkabau heartland into mainland Southeast Asia.

This version of the story links it with Burhanuddin Ulakan, a Minangkabau man who studied in Aceh and became the first Muslim preacher in West Sumatra.

As narrated in the Malay Annals, the beginning of the Sumatran empire, started with a story of Paduka Demang Lebar Daun and Sang Nila Utama which took place in Batang Musi River.

Paduka Demang Lebar Daun was officially styled as the forefather (Mangkubumi) of the Nusantara peoples in Malay archipelago by Sang Nila Utama through their oath.

At some point or another they came into contact with the Thais, Malays, Toraja, Han Chinese, Bugis, Moluccans, Madurese, Dayaks, Sulu, Burmese and orang asli until they spread across the Indonesian Archipelago.

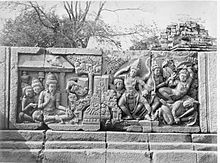

[14] Images of Hindu figures such as Durga, Krishna and scenes from the Ramayana all bear testament to the Indian influence on local weapons and armour.

Silat was and in some cases still is used by the defence forces of various Southeast Asian kingdoms and states in what are now Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Vietnam, Thailand and Brunei.

True piracy saw an increase after the arrival of the European colonists, who recorded Malay pirates armed with sabres, kris and spears across the archipelago even into the Gulf of Siam.

Marooned Cantonese and Hokkien naval officers would set up small gangs for protection along river estuaries and recruit local silat practitioners as foot soldiers known as lang or lanun (Malay for pirate).

Silat shares many similarities with Okinawan karate as well as the throws and stances of weapon-based Japanese martial arts[15] which probably date back to this time.

Trade with Japan ended when the country went into self-imposed isolation but resumed during the Meiji era, during which time certain areas of Malaysia, Indonesia and Singapore became home to a small Japanese population.

Except for some weapon-based styles, students must generally achieve a certain degree of skill before being presented with a weapon which is traditionally made by the guru.

Unlike eskrima, silat does not necessarily emphasise armed combat and practitioners may choose to focus mainly on fighting empty-handed.

Silat's traditional arsenal is largely made up of objects designed for domestic purposes such as the flute (seruling), rope (tali), sickle (sabit) and chain (rantai).

Every style of silat incorporates multi-level fighting stances (sikap pasang), or preset postures meant to provide the foundation for remaining stable while in motion.

Beginners once had to practice this stance for long periods of time, sometimes as many as four hours, but today's practitioners train until it can be easily held for at least ten minutes.

Their main function is to pass down all of a style's techniques and combat applications in an organised manner, as well as being a method of physical conditioning and public demonstration.

In the Minangkabau area silat is one of the main components in the men's folk dance called randai,[19] besides bakaba (storytelling) and saluang jo dendang (song-and-flute).

The instruments vary from one region to another but the gamelan (Javanese orchestra), kendang or gendang (drum), suling (flute) and gong are common throughout Southeast Asia.

Indonesian action stars Ratno Timoer and Advent Bangun were famous for 80s silat films such as The Devil's Sword and Malaikat Bayangan.

After the year 2000, silat was featured to varying degrees of importance in popular Malay movies such as Jiwa Taiko, Gong, KL Gangster, Pontianak Harum Sundal Malam, and the colour remake of Orang Minyak.

In Malaysia, this genre is said to have reached its peak during the 1990s when directors like Uwei Shaari strove to depict silat in its original form by casting martial artists rather than famous actors.

Aside from period dramas, authentic silat is often featured in other genres, such as the Indonesian series Mawar Merah and the made-for-TV children's movie Borobudur.

In Malaysia, various styles of silat are regularly showcased in martial arts-themed documentary serials like Mahaguru, Gelanggang and Gerak Tangkas.

Outside Asia, silat was referenced in Tom Clancy's Net Force by Steve Perry, although the books give a fictionalized portrayal of the art.

The earliest instance of silat in graphic novels are found in Indonesian comics of the 1960s which typically featured heroes that were expert martial artists.

The titles Si Buta Dari Gua Hantu, Jaka Sembung, Panji Tengkorak and Walet Merah all gave rise to popular films in the 1970s and 80s.

The most well-known Indonesian radio shows began in the 1980s, all of them historical dramas concerning the adventures of martial artists in Hindu-Buddhist kingdoms of medieval Java and Sumatra.