Simians (Chinese poetry)

Simians of various sorts (including the monkey, gibbon, and other primates of real or mythological nature) are an important motif in Chinese poetry.

The gibbon type of simian was widespread in Central and Southern China, until at least the Song Dynasty; later deforestation and other habitat reduction severely curtailed their range.

Their range has included all of China (by definition) from thousands of years ago, through medieval times, and into the present; although, with greater population densities near ocean coasts and river banks.

In poetry, humans may be metaphorically alluded to by implicitly comparative reference to other simians: this is generally a pejorative allusion.

Other examples include life in the environs of the heavily restricted confinement areas often made as habitats for concubines or wives, and the poorly supplied and frequently violent fortified mountain passes and frontier fortresses, cases in which themes of human-environmental dissonance developed into their own genres.

Besides a certain pre-modern lack of modern bioscientific taxonomic precision, records of Chinese language usage in references to various simian species show evidence of variability over the ages.

Other vocabulary distinctions include: 猱 (Hanyu Pinyin: náo, Tang: nɑu), referring to simians of yellow hair, 猩猩 (Hanyu Pinyin: xīngxīng, Tang: *shræng-shræng, Schafer: hsing-hsing) is used to refer to a simian which Edward Schafer believes to refer to gibbons of various species, whose (somewhat mythologized) blood was referenced in relationship to describing a vivid red-coloured dye (the term fei-fei also confusedly encountered in this context: 狒狒 (Hanyu Pinyin: fèifèi, Tang: bhiə̀i-bhiə̀i or *b'jʷe̯i-b'jʷe̯i).

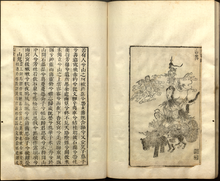

One of the earliest collections of Chinese Poetry is the Chu Ci anthology, which contains poems from the Warring States period through the Han Dynasty.

The classical tradition of the poet-in-exile originates with the archetypal protagonist Qu Yuan singing sad stanzas of poetry while wandering in the wilderness of Chu, lamenting his fate.

Travel between the Sichuan Basin and the rest of what were then the other more populated areas of China was most frequently done by boat trips during which the poets or other passengers experienced the difficulties of navigating dangerous waterways, above which soared the dramatically scenic heights of Wushan, while their ears were impressed by the loud sounds of the indigenous population of gibbons and/or other simians.

The poet invokes the sound and image of simians while singing to his muse, in the poem's concluding lines (Hawkes translation, 116): From its time of first publication, this particular type of imagery from the Chu Ci would prove be an enduring one in Chinese literature through the ensuing ages.

Wang Wei refers to this (using the character 猿, [yuán], for "gibbon"), in a poem describing his Lantian (藍田/蓝田, literally, Indigo Field) home to an imperial inspector in charge of royal acquisitions of parks and forests who had traveled out to Lantian, "Composed in reply to Secretary So of the Board of Concern who passed by the villa at Indigo Field but did not stay" (Stimson, 39).

For one, this poem deprecates (though in the tradition of polite Chinese humility) the quality of Wang's Lantian estate, describing it in this poem as a "poor dwelling", located so far from civilization that it is characterized by the occasional fire from camping hunters, the occasional fishing boat frozen to the icy shore, sparsely sounding temple bells, and the sounds of gibbons howling in the night (and thus, obviously unsuitable for inclusion into the royal domains): this is in marked contrast to the playful exaggerations of Wang's and Pei Di's lavish descriptions of the same Lantian estate in the Wangchuan ji collection, in which the pair of poets depict Wang's country home as being replete with a royal hunting park for deer, a gold dust spring, and various other fabulous establishments (Wangchuan was a poetic term used for Wang's abode in Lantian).

Another version of translation: Leaving at dawn the White Emperor crowned with cloud, I've sailed a thousand li through canyons in a day.

(NOTE: "Baidi" literally means "White Emperor") John C. H. Wu (1972:75) has another version of the translation of the third line, which goes: (before the boat had already brought the poet back from exile).

Du wrote his poem at one of his stops along the way in this area: Kui Prefecture was located in what is now Chongqing, in the Yangzi River basin.

Many of the Chinese poems from the Tang and Song dynasty emphasize the presence of simian beings, in part, like Du Fu in "Autumn Day in Kui Prefecture", to emphasize the exotic and uncivilized nature which they perceived and associated with the Xiaoxiang area, including the local incomprehensible languages, unfamiliar Chinese dialects, and rural subsistence culture.

The word "simian" has roots in Latin which extend back to ancient Greek, and thus is part of a tradition which predates and defies modern biological taxonomic classification, except in the broadest terms.

Several Tang poets used the term in poetic imagery, including a couple of poems by Zhang Ji of Jiangnan (See, Schafer, 208–210, 234, and note 12 page 328).