Simón Bolívar

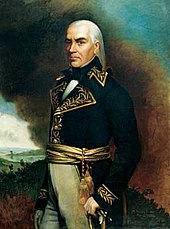

Simón José Antonio de la Santísima Trinidad Bolívar Palacios Ponte y Blanco[c] (24 July 1783 – 17 December 1830) was a Venezuelan statesman and military officer who led what are currently the countries of Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Peru, Panama, and Bolivia to independence from the Spanish Empire.

[31] Bolívar promised the Real Audiencia that he would focus on his education and was subsequently taught full-time by Rodríguez and the Venezuelan intellectuals Andrés Bello and Francisco de Andújar [es].

[62] In March 1804, the municipal authorities of Madrid ordered all non-residents in the city to leave to alleviate a bread shortage brought about by Spain's resumed hostilities with Britain.

[63][64] Over April, Bolívar and Fernando Rodríguez del Toro [es], a childhood friend and relative of his wife, made their way to Paris and arrived in time for Napoleon to be proclaimed Emperor of the French on 18 May 1804.

While in Paris, Bolívar began a dalliance with the Countess Dervieu du Villars,[66] at whose salon he likely met the naturalists Alexander von Humboldt and Aimé Bonpland, who had traveled through much of Spanish America from 1799 to 1804.

[71] From Milan, they traveled down the Po Valley to Venice, then to Florence, and then finally Rome,[72] where Bolívar met, among others, Pope Pius VII, French writer Germaine de Staël, and Humboldt again.

On 18 August 1805, when he, del Toro, and Rodríguez traveled to the Mons Sacer, where the plebs had seceded from Rome in the 4th century BC, Bolívar swore to end Spanish rule in the Americas.

[74] By April 1806, Bolívar had returned to Paris and desired passage to Venezuela,[75] where Venezuelan revolutionary Francisco de Miranda had just attempted an invasion with American volunteers.

[118] After it was discovered that one of the men leading the congress was a Spanish agent who had escaped with military documents, however,[119] discourse – which Bolívar was prominent in – changed decidedly in favor of independence over 3 and 4 July.

It had a weak base of support and enemies in conservative whites, disenfranchised people of color, and the already hostile Venezuelan provinces, which received troops and supplies from the Captaincy-Generals of Puerto Rico and Cuba.

Miranda,[138] retreating east with a disintegrating army,[139] ordered Bolívar to assume command of the coastal city of Puerto Cabello and its fortress,[140] which contained Royalist prisoners and most of the republic's remaining arms and ammunition.

Late in October, the exiles arranged for passage west to the city of Cartagena to offer their services as military leaders to the United Provinces of New Granada against the Royalists.

[181] The republic was assailed from all sides by slave revolts and Royalist forces,[182] especially the Legion of Hell, an army of llaneros – the horsemen of the Llanos, to the south – led by the Spanish warlord José Tomás Boves.

[205] He left Jamaica eight days later,[206] arrived in Les Cayes on 24 December,[207] and on 2 January 1816 was introduced to Alexandre Pétion, President of the Republic of Haiti by a mutual friend.

[256][262] In May, as the annual wet season was beginning in the Llanos, Bolívar met with his officers and revealed his intention to invade and liberate New Granada from Royalist occupation,[263] which he had prepared for by sending Santander to build up Republican forces in Casanare Province in August 1818.

[273] After a brief convalescence, the Republicans made rapid progress against the forces of Spanish colonel José María Barreiro Manjón until, on 7 August, the Royalists were routed at the Battle of Boyacá.

[286] Meanwhile, Morillo's military and political position was fatally undermined by the mutiny of Spanish soldiers in Cádiz on 1 January [es], which forced Ferdinand VII to accept a liberal constitution in March.

[300] Bolívar entered Caracas in triumph on 29 June,[301] and issued a decree on 16 July dividing Venezuela into three military zones governed by Páez, Bermúdez, and Mariño.

[323][324] Over the rest of 1822, Bolívar traveled around Ecuador to complete its annexation while dispatching officers to suppress repeated rebellions in Pasto and resisting calls to return to Bogotá or Venezuela.

Accepting the extension,[348] Bolívar settled into governing Peru and passing reforms that were largely not carried out, such as a school system based on the principles of English educator Joseph Lancaster that was managed by Simón Rodríguez.

[350] Bolívar arrived in Potosí on 5 October and met with two Argentine agents, Carlos María de Alvear and José Miguel Díaz Vélez, who tried without success to convince him to intervene in the Cisplatine War against the Empire of Brazil.

[356] In Venezuela, Páez revolted against Santander, and in Panama, a congress of American nations organized by Bolívar convened without his attendance and produced no change in the hemispheric status quo.

On 3 September, responding to pleas for his return to Colombia, Bolívar departed Peru and left it under a governing council led by Bolivian general Andrés de Santa Cruz.

[360] On 25 November, Bolívar left Bogotá with an army supplied by Santander and arrived at Puerto Cabello on 31 December,[361] where he issued a general amnesty to Páez and his allies if they submitted to his authority.

[364] Meanwhile, the Colombian soldiers garrisoned in Lima mutinied, arrested their Venezuelan officers, and occupied Guayaquil until September 1827, allowing Bolívar's opponents in Peru to depose him as president and repeal his constitution.

Padilla, though uninvolved with the attempted coup, was executed for treason for his earlier rebellion; Santander, whom Bolívar thought responsible for the plot, was pardoned but exiled from Colombia.

[371] In December 1828, Bolívar left Bogotá to respond to Peru's intervention in Bolivia and invasion of Ecuador and a revolt in Popayán and Pasto led by José María Obando.

[379] With his health deteriorating and no ship forthcoming, Bolívar was moved by his staff to Barranquilla in October and then, at the invitation of a Spanish landowner in the area, to the Quinta de San Pedro Alejandrino near Santa Marta.

[386][389][390] Bolívar's personal beliefs were liberal and republican, and formed by Classical and Enlightenment philosophy;[391] among his favorite authors were Hobbes, Spinoza, the Baron d'Holbach, Hume, Montesquieu, and Rousseau.

"[405] Bolívar is the preeminent symbol of Latin America and the focus of what could seem almost unrivaled posthumous attention, seen from his own times forward as a force now for liberalism or other forms of modernity, now for old regime values and authoritarianism, now for a mix of the two, with the debate over the meaning of his figure having no end in sight.