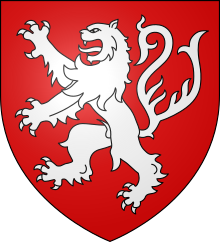

Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester

Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester (c. 1208 – 4 August 1265), later sometimes referred to as Simon V[nb 1] de Montfort to distinguish him from his namesake relatives, was an English nobleman of French origin and a member of the English peerage, who led the baronial opposition to the rule of King Henry III of England, culminating in the Second Barons' War.

Following his initial victories over royal forces, he became de facto ruler of the country,[5] and played a major role in the constitutional development of England.

With the irrevocable loss of Normandy, King John refused to allow the elder Simon to succeed to the earldom of Leicester and instead placed the estates and title into the hands of Montfort senior's cousin Ranulf, the Earl of Chester.

The elder Simon had also acquired vast domains during the Albigensian Crusade, but was killed during the Siege of Toulouse in 1218 and his eldest son Amaury was not able to retain them.

When Amaury was rebuffed in his attempt to get the earldom back, he agreed to allow his younger brother Simon to claim it in return for all family possessions in France.

Henry was in no position to confront the powerful Earl of Chester, so Simon approached the older, childless man himself and persuaded him to cede him the earldom.

As a younger son, Simon de Montfort attracted little public attention during his youth, and the date of his birth remains unknown.

The idea of an alliance between the rich County of Flanders and a close associate of Henry III of England did not sit well with the French crown.

The French Queen Dowager Blanche of Castile convinced Joan to marry Thomas II of Savoy instead, who himself became Count of Flanders.

When Simon and Eleanor's first son was born in November 1238 (despite rumours, more than nine months after the wedding), he was baptised Henry in honour of his royal uncle.

[17] Leicester's Jews were allowed to move to the eastern suburbs, which were controlled by Montfort's great-aunt Margaret, Countess of Winchester.

[20][21][22] Robert Grosseteste – then Archdeacon of Leicester and, according to Matthew Paris, de Montfort's confessor[23] – may have encouraged the expulsion, though he is known to have argued that Jews' lives should be spared.

Montfort owed a great sum of money to Thomas, Count of Flanders, Queen Eleanor's uncle, and named King Henry as security for his repayment.

He was part of the crusading host which, under Richard of Cornwall, negotiated the release of Christian prisoners including Simon's older brother, Amaury.

Bitter complaints were excited by the rigour with which Montfort suppressed the excesses of the Seigneurs and of contending factions in the great communes.

The earl preferred to make his peace with Henry III, which he did in 1253, in obedience to the exhortations of the dying Robert Grosseteste, Bishop of Lincoln.

He undertook, with Peter of Savoy, the Queen's uncle, the difficult task of extricating the king from the pledges which he had given to the Pope with reference to the Crown of Sicily; and Henry's writs of this date mention Montfort in friendly terms.

[30] Simon de Montfort returned to England in 1263, at the invitation of the barons who were now convinced of the king's hostility to all reform, and raised a rebellion with the avowed object of restoring the form of government which the Provisions had ordained.

Measures against the Jews and controls over debts and usury dominated debates about royal power and finances among the classes that were beginning to be involved in Parliament.

Simon was prevented from presenting his case to Louis directly on account of a broken leg, but few suspected that the king of France, known for his innate sense of justice, would completely annul the Provisions in his Mise of Amiens in January 1264.

Henry retained the title and authority of King, but all decisions and approval now rested with his council, led by Montfort and subject to consultation with parliament.

Montfort, who was in that parliament, took the innovation further by including ordinary citizens from the boroughs, also elected, and it was from this period that parliamentary representation derives.

The list of boroughs which had the right to elect a member grew slowly over the centuries as monarchs granted charters to more English towns.

The final nail was the defection of Gilbert de Clare, the Earl of Gloucester, the most powerful baron and Simon's ally at Lewes.

Though boosted by Welsh infantry sent by Montfort's ally Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, Simon's forces were severely depleted.

Prince Edward attacked his cousin, his godfather's son Simon's forces at Kenilworth, capturing more of Montfort's allies.

"[42] Before the battle, Prince Edward had appointed a twelve-man death squad to stalk the battlefield, their sole aim being to find the earl and cut him down.

"[citation needed] Following Montfort's death, he became the focus of an unofficial popular miracle cult, centred on his grave in Evesham Abbey.

[52] Jews were living in such terror that King Henry appointed burgesses and citizens of certain towns to protect and defend them because "they fear[ed] grave peril" and were in a "deplorable state.

In 1965, a memorial of stone from Montfort-l'Amaury was laid on the site of the former altar by Speaker of the House of Commons Sir Harry Hylton-Foster and Archbishop of Canterbury, Michael Ramsey.