Simplicius of Cilicia

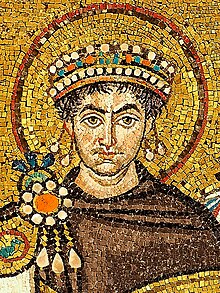

He was among the pagan philosophers persecuted by Justinian in the early 6th century, and was forced for a time to seek refuge in the Persian court, before being allowed back into the empire.

Although his writings are all commentaries on Aristotle and other authors, rather than original compositions, his intelligent and prodigious learning makes him the last great philosopher of pagan antiquity.

[12] Seven philosophers, among whom were Simplicius, Eulamius, Priscian, and others, with Damascius, the last president of the Platonist school in Athens at their head, resolved to seek protection at the court of the famous Persian king Chosroes, who had succeeded to the throne in 531.

Only at the end of his explanation of the treatise of Epictetus, Simplicius mentions, with gratitude, the consolation which he had found under tyrannical oppression in such ethical contemplations; which might suggest that it was composed during, or immediately after, the above-mentioned persecutions.

Simplicius, as a Neoplatonist, endeavoured to show that Aristotle agrees with Plato even on those points which he controverts, so that he may lead the way to their deeper, hidden meaning.

In other respects, too, he postulated a fundamental agreement between the core ideas of the important philosophical teachers and directions, insofar as they seemed to be compatible with the Neoplatonic world view.

He is, however, distinguished from his predecessors, whom he so admires, in making less frequent application of Orphic, Hermetic, Chaldean, and other Theologumena of the East; partly in proceeding carefully and modestly in the explanation and criticism of particular points, and in striving with diligence to draw from the original sources a thorough knowledge of the older Greek philosophy.

He believed that astronomers should not be satisfied with devising "hypotheses" – mere rules of calculation – but should use a physical theory well founded by causal argumentation as the starting point for their considerations.

Thus, place is not a neutral space in which objects happen to be located, but is the principle of the ordered structure of the entire cosmos and each individual thing.

He defended the Aristotelian doctrine of the eternity and indestructibility of the cosmos against the position of John Philoponus, who, as a Christian, accepted creation as the temporal beginning and a future end of the world and justified his view philosophically.

Simplicius also took a stand on this problem and defended Neoplatonic monism against Manichaeism, a religious doctrine that had been widespread since the 3rd century and offered a decidedly dualistic explanation of the bad.

Moreover, Simplicius accused the Manichaeans of taking away from man the realm of what fell within his competence because it relieved him of the responsibility for his ethical decisions and oaths.

A person's bad actions can then no longer be traced back to himself, because in this case he is exposed to an overpowering influence and his self-determination is revoked.

Thus genuine evil does not exist in the nature surrounding man, nor in his circumstances, but only in his soul, and there it can be eliminated through knowledge and a philosophical way of life.

According to the world view of the pagan philosophers of the time, Simplicius believed that becoming and passing away only take place in the "sublunar" space – below the moon.

He wanted to bring Epictetus's stoic guide to a philosophical life closer to his readers who were influenced by the Platonic-Aristotelian way of thinking.

Simplicius saw his task as a commentator as helping the reader to better understand what "is up to us," and placed great emphasis on the distinction between what is within our power and responsibility and what is beyond his control.

It is at the mercy of unreasonable impulses, strives unbridled for sensual pleasure and develops unnecessary fear due to false ideas.

In addition, we have to thank him for such copious quotations from the Greek commentaries from the time of Andronicus of Rhodes down to Ammonius and Damascius, that, for the Categories and the Physics, the outlines of a history of the interpretation and criticism of those books may be composed.

With a correct idea of their importance, Simplicius made the most diligent use of the commentaries of Alexander of Aphrodisias and Porphyry; and although he often enough combats the views of the former, he knew how to value, as it deserved, his (in the main) sound critical sense.

He has also preserved for us intelligence of several more ancient readings, which now, in part, have vanished from the manuscripts without leaving any trace, and in the paraphrastic sections of his interpretations furnishes us with valuable contributions for correcting or settling the text of Aristotle.

He mentioned the name of Simplicius among mathematicians and astronomers, but also attributed to him a commentary on De Anima, which had been translated into Classical Syriac and also existed in Arabic.

[50] The Latin-speaking Late Medieval scholars of Western and Central Europe only had two writings by Simplicius: the commentaries on the Categories and on On the Heavens, which William of Moerbeke had translated into Latin.

Earlier – in the period 1235–1253 – Robert Grosseteste had made a partial translation of the Commentary on On the Heavens[51] which had a strong influence on philosophers including Thomas Aquinas, Henry of Ghent, Aegidius Romanus and Johannes Duns Scotus.

[45][52] Petrus de Alvernia used in his commentary on Über den Himmel a wealth of material from the relevant work of his ancient predecessor, and Heinrich Bate in his great handbook Speculum Divinorum et Quorundam Naturalium partly agreeing, partly disagreeing with the theses put forward by Simplicius in his commentary on On the Heavens[53] rather than relying on the authority of Simplicius.

[54] The Byzantine princess Theodora Rhaulaina, a niece of Emperor Michael VIII, copied the Physics commentary of Simplicius in the period 1261–1282.

From this point of view, Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff judged that the "excellent Simplicius" had been "a good man" and that the world could never thank him enough for the preservation of fragments from lost older works.

[58] Simplicius' own philosophical achievement received less attention; the disdain that was widespread in the 19th and early 20th centuries for late antique Neoplatonism, which was then notorious for being too speculative, stood in the way of an unbiased assessment.

[59] Eduard Zeller[60] (1903) found the commentaries to be "the work of great diligence and comprehensive erudition" and offer a "careful and mostly reasonable explanation" of the texts interpreted.

However, Zeller considered Simplicius' denial of considerable contradictions between Aristotle and Plato to be completely wrong, characterizing as someone a thinker who hardly made an original philosophical achievement, but was only "the thinking editor of a given teaching that has come to its conclusion in all essential respects".