Theology of Martin Luther

In the centuries leading up to the Reformation, an "Augustinian Renaissance" revived interest in the thought of Augustine of Hippo (354-430).

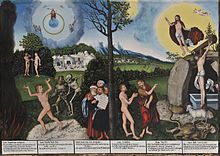

For the Lutheran tradition, the doctrine of salvation by grace alone through faith alone in Christ alone is the material principle upon which all other teachings rest.

Luther's study and research led him to question the contemporary usage of terms such as penance and righteousness in the Roman Catholic Church.

He became convinced that the church had lost sight of what he saw as several of the central truths of Christianity — the most important being the doctrine of justification by faith alone.

[16] As a result of his lectures on the Psalms and Paul the Apostle's Epistle to the Romans, from 1513–1516, Luther "achieved an exegetical breakthrough, an insight into the all-encompassing grace of God and all-sufficient merit of Christ.

The doctrine of salvation by God's grace alone, received as a gift through faith and without dependence on human merit, was the measure by which he judged the religious practices and official teachings of the church of his day and found them wanting.

All have sinned and are justified freely, without their own works and merits, by His grace, through the redemption that is in Christ Jesus, in His blood (Romans 3:23-25).

Therefore, it is clear and certain that this faith alone justifies us...Nothing of this article can be yielded or surrendered, even though heaven and earth and everything else falls (Mark 13:31).

He believed that this principle of interpretation was an essential starting point in the study of the scriptures and that failing to distinguish properly between Law and Gospel was at the root of many fundamental theological errors.

Through his studies, Luther recognized that the hierarchical division of Christians into clergy and laity, stood in contrast to the Apostle Peter's teaching (1Peter 2:1-10).. .

9But you are a chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, a people for his own possession, that you may proclaim the excellencies of him who called you out of darkness into his marvelous light.

18th century philosopher Immanuel Kant's doctrine of radical evil has been described as an adaptation of the Lutheran simul justus et peccator.

This distinction has in Lutheran theology often been related to the idea that there is no particular Christian contribution to political and economic ethics.

[28] Mannermaa's student Olli-Pekka Vainio has argued that Luther and other Lutherans in the sixteenth century (especially theologians who later wrote the Formula of Concord) continued to define justification as participation in Christ rather than simply forensic imputation.

Rather, the Finnish School asserts that Luther's doctrine of salvation was similar to that of Eastern Orthodoxy, theosis (divinization).

The Finnish language is deliberately borrowed from the Greek Orthodox tradition, and thus it reveals the intention and context of this theological enterprise: it is an attempt by Lutherans to find common ground with Orthodoxy, an attempt launched amid the East-West détente of the 1970s, but taking greater impetus in a post-1989 world as such dialogue appears much more urgent for churches around the Baltic.

For instance, during his Table Talks, he references Mechthild of Magdeburg's The Flowing Light of the Godhead, an example of the pre-reformation piety which Luther was immersed in that associate the Devil with excrement.

Luther references Mechtihild's work, suggesting that those in a state of mortal sin are eventually excreted by the Devil.