Harry Lauder

Sir Henry Lauder (/ˈlɔːdər/; 4 August 1870 – 26 February 1950)[1] was a Scottish singer and comedian popular in both music hall and vaudeville theatre traditions; he achieved international success.

He was described by Sir Winston Churchill as "Scotland's greatest ever ambassador",[2][3][4] who "... by his inspiring songs and valiant life, rendered measureless service to the Scottish race and to the British Empire.

"[5] He became a familiar worldwide figure deploying his kilt and cromach (walking stick) as icons of Scottishness to huge acclaim, especially in America.

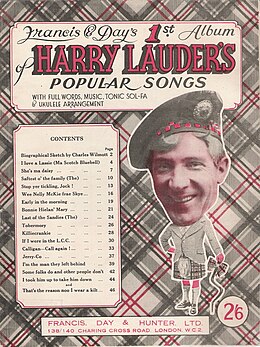

Lauder usually performed in full Highland regalia—kilt, sporran, tam o' shanter, and twisted walking stick, and sang Scottish-themed songs.

He made his first public appearance, singing, at a variety concert at Oddfellows' Hall in Arbroath when he was 13 years old, winning first prize for the night (a watch).

[15] In 1884 the family went to Hamilton, South Lanarkshire, to live with Isabella's brother, Alexander, who found Harry employment at Eddlewood Colliery at ten shillings per week; he kept this job for a decade.

[16] On 8 January 1910, the Glasgow Evening Times reported that Lauder had told the New York World that, during his mining career: I was entombed once for 6 long hours.

Lauder said he was "proud to be old coal-miner" and in 1911, became an outspoken advocate, "pleading the cause of the poor pit ponies" to Winston Churchill, when introduced to him at the House of Commons and later reported to the Tamworth Herald that he "could talk for hours about my wee four-footed friends of the mine.

But I think I convinced that the time has now arrived when something should be done by the law of the land to improve the lot and working conditions of the patient, equine slaves who assist so materially in carrying on the great mining industry of this country.

He received further engagements including a weekly "go-as-you please" night held by Mrs. Christina Baylis at her Scotia Music Hall/Metropole Theatre in Glasgow.

[19] By 1894, Lauder had turned professional and performed local characterisations at small, Scottish and northern English music halls but had ceased the repertoire by 1900.

In March of that year, Lauder travelled to London and reduced the heavy dialect of his act which according to a biographer, Dave Russell, "handicapped Scottish performers in the metropolis".

He was an immediate success at the Charing Cross Music Hall and the London Pavilion, venues at which the theatrical paper The Era reported that he had generated "great furore" among his audiences with three of his self-composed songs.

[1] In 1905 Lauder's success in leading the Howard & Wyndham pantomime at the Theatre Royal, Glasgow, for which he wrote I Love a Lassie, made him a national star, and he obtained contracts with Sir Edward Moss and others.

[22] He was paid £1125 for an engagement at the Glasgow Pavilion Theatre in 1913 and was later considered by the press to earn one of the highest weekly salaries by a theatrical performer during the prewar period.

[25] Following the December 1916 death of his son on the Western Front; Lauder led successful charity fundraising efforts, organised a recruitment tour of music halls and entertained troops in France with a piano.

[26] Through his efforts in organising concerts and fundraising appeals he established the charity, the Harry Lauder Million Pound Fund,[27][28] for maimed Scottish soldiers and sailors, to help servicemen return to health and civilian life;[29] and he was knighted in May 1919 for Empire service during the War.

He briefly emerged from retirement to entertain troops during the Second World War and make wireless broadcasts with the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra.

[44] Lauder departed Sydney for the USA on board the liner SS Ventura on Saturday 27 July 1929,[45] a ship he was familiar with.

Over twenty thousand people had lined the streets for hours beforehand and it was reported that every policeman in the city plus mounted police were required to keep order.

[51][52] He wrote a number of books, which ran into several editions, including Harry Lauder at Home and on Tour (1912), A Minstrel in France (1918),[53] Between You and Me (1919), Roamin' in the Gloamin' (1928 autobiography),[54] My Best Scotch Stories (1929), Wee Drappies (1931) and Ticklin' Talks (circa 1932).

[56] In 1927 Victor promoted Lauder recordings to their Red Seal imprint, making him the only comedic performer to appear on the label primarily associated with operatic celebrities.

[55][57] Lauder is one of three artists shown on Victor's black, purple, blue and red Seal records (the others being Lucy Isabelle Marsh and Reinald Werrenrath).

[24] He wrote the song "The End of the Road" (published as a collaboration with the American William Dillon, 1924) in the wake of John's death, and built a monument for him in the private Lauder cemetery in Glenbranter.

[67] She was buried next to her son's memorial in the private Lauder cemetery on the 14,000 acre Glenbranter estate in Argyll,[68] where her parents would later join her.

[79] Lauder's first command performance before Edward VII is satirised by Neil Munro in his Erchie Macpherson story "Harry and the King", first published in the Glasgow Evening News of 14 September 1908.

Websites carry much of his material and the Harry Lauder Collection, amassed by entertainer Jimmy Logan, was bought for the nation and donated to the University of Glasgow.

On 29 September 2007, Lauder-Frost rededicated the Burslem Golf Course & Club at Stoke-on-Trent, which had been formally opened exactly a century before by Harry Lauder.