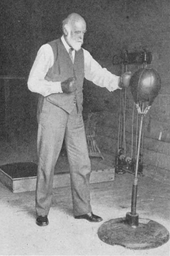

Oliver Lodge

Sir Oliver Joseph Lodge (12 June 1851 – 22 August 1940) was an English physicist whose investigations into electromagnetic radiation contributed to the development of radio communication.

His parents were Oliver Lodge (1826–1884) – later a ball clay merchant[note 1] at Wolstanton, Staffordshire – and his wife, Grace, née Heath (1826–1879).

At Chatterley House, just a mile south of Etruria Hall where Wedgwood had experimented, Lodge's Autobiography recalled that "something like real experimentation" began for him around 1869.

[3] Lodge left the Potteries in 1881 to up take the post of Professor of Physics and Mathematics at the newly founded University College, Liverpool.

Lodge was awarded the Rumford Medal of the Royal Society in 1898, and was knighted in the 1902 Coronation Honours,[4] receiving the accolade from King Edward VII at Buckingham Palace on 24 October that year.

But Lodge was fairly limited in mathematical physics both by aptitude and training, and his first two papers were a description of a mechanism (of beaded strings and pulleys) that could serve to illustrate electrical phenomena such as conduction and polarization.

Indeed, Lodge is probably best known for his advocacy and elaboration of Maxwell's aether theory – a later deprecated model postulating a wave-bearing medium filling all space.

Second, his good friend George FitzGerald (on whom Lodge depended for theoretical guidance) assured him (incorrectly) that "ether waves could not be generated electromagnetically.

"[6] FitzGerald later corrected his error, but, by 1881, Lodge had assumed a teaching position at University College, Liverpool the demands of which limited his time and his energy for research.

Lodge took the opportunity to carry out a scientific investigation, simulating lightning by discharging Leyden jars into a long length of copper wire.

"[7][10] On 1 June 1894, during a Friday Evening Discourse at the Royal Institution of Great Britain, Lodge gave a memorial lecture on the work of Hertz (recently deceased) and the German physicist's proof of the existence of electromagnetic waves 6 years earlier.

[11] Later in June he repeated his lecture, and on 14 August 1894 at the meeting for the British Association for the Advancement of Science at Oxford University he was able to increase the distance of transmission up to 55 meters (180').

When the small electrical charge from waves from an antenna were applied to the electrodes, the metal particles would cling together or "cohere" causing the device to become conductive allowing the current from a battery to pass through it.

At the time of the dispute some, including the physicist John Ambrose Fleming, pointed out that Lodge's lecture was a physics experiment, not a demonstration of telegraphic signaling.

[12] In 1886 Lodge developed the moving boundary method for the measurement in solution of an ion transport number, which is the fraction of electric current carried by a given ionic species.

[16] Lodge carried out scientific investigations on the source of the electromotive force in the Voltaic cell, electrolysis, and the application of electricity to the dispersal of fog and smoke.

[17] In 1898, Lodge gained a patent on the moving-coil loudspeaker, utilizing a coil connected to a diaphragm, suspended in a strong magnetic field.

[22] In his 1913 Presidential Address to the Association, he affirmed his belief in the persistence of the human personality after death, the possibility of communicating with disembodied intelligent beings, and the validity of the Aether theory.

Philosopher Paul Carus wrote that the "story of Raymond's communications rather excels all prior tales of mediumistic lore in the silliness of its revelations.

But the saddest part of it consists in the fact that a great scientist, no less a one than Sir Oliver Lodge, has published the book and so stands sponsor for it.

As a Christian Spiritualist, Lodge had written that the resurrection in the Bible referred to Christ's etheric body becoming visible to his disciples after the Crucifixion.

[33] Edward Clodd criticized Lodge as being an incompetent researcher to detect fraud and claimed his Spiritualist beliefs were based on magical thinking and primitive superstition.

[36] Magician John Booth noted that the stage mentalist David Devant managed to fool a number of people into believing he had genuine psychic ability who did not realize that his feats were magic tricks.

They had twelve children, six boys and six girls, including Oliver William Foster, Alexander (Alec), Francis Brodie, Lionel and Noel.

His obituary in The Times wrote:[41] Always an impressive figure, tall and slender with a pleasing voice and charming manner, he enjoyed the affection and respect of a very large circle… Lodge's gifts as an expounder of knowledge were of a high order, and few scientific men have been able to set forth abstruse facts in a more lucid or engaging form… Those who heard him on a great occasion, as when he gave his Romanes lecture at Oxford or his British Association presidential address at Birmingham, were charmed by his alluring personality as well as impressed by the orderly development of his thesis.

But he was even better in informal debate, and when he rose, the audience, however perplexed or jaded, settled down in a pleased expectation that was never disappointed.Lodge's letters and papers were divided after his death.