Ski boot

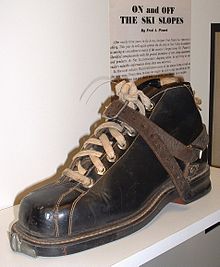

[2] Boots with the sole extended rearward to produce a flange for the cable to firmly latch to become common, as did designs with semi-circular indentations on the heel for the same purpose.

A key development was the invention in 1928 of the Kandahar cable binding, which attached the heel solidly to the ski and used a strong spring to pull the boot forward into the toe iron.

In 1956, the Swiss factory Henke introduced the buckle boot, using over-center levered latches patented by Hans Martin to replace laces.

To spread it back out again, the boots featured C-shaped flaps that stretched over the opening where the laces would be, to the side where the buckles were located.

Early examples used a lace-up design, but in 1964 he combined a new, more flexible polyurethane plastic with the overlapping flap and buckle system from Henke to produce the first recognizably modern ski boot.

Production examples appeared in 1966, and when Nancy Greene started winning races on them, the plastic boot became a must-have item.

[7] Over time the cuff around the leg evolved upward, starting just over the ankle like leather boots, but rising to a point about halfway to the knee by the 1980s.

This leads to shell modification services, when the boot is stretched to fit the skier's foot, typically by heating the plastic and pressing it into place.

Closing a cable locks the moving rear portion forward onto the front half, forming the stiff cuff that pivots around rivets at the ankle like a conventional front-entry design.

As the toe area is a single piece and lacks buckles for adjustment, rear-entry boots may have considerable "slop", and various systems of cables, plates or foam-filled bladders were used to address this.

The rear entry design fell from popularity in the 1990s due to their shunning by racers in search of a closer fit.

The big advantage was that the main shell was a single piece that was convex at all points, meaning it could be easily produced using a plug mould.

The open cuff (the "throat") makes the boots easy to get on and off, and the shaping of the tongue allows complete control over the forward flex.

These were widespread in the late 1960s, especially from the large collection of Italian bookmakers in Montebelluna, before they started introducing all-plastic designs of their own.

Typical designs used a plastic insert wrapping around the heel area and extending up to just below the ankle, allowing the skier to force their foot sideways and offering some edging control.

Others, notably 1968's Raichle Fibre Jet, wrapped a soft leather boot in an external fibreglass shell, producing a side-entry design that was not particularly successful.

Stepping in was very easy, simply sliding the foot sideways in through the opening, then swinging the flap closed and stretching a fabric cover over it to seal it.

GripWalk (ISO 23223) is a modification of the traditional flat-bottomed alpine boot with a rockered rubber sole, allowing improved traction and walking ability on slippery or uneven surfaces.

A new Salomon Pilot binding is now widely used for racing because it uses two connection points so that the skier has more stability and control over the ski.

As these boots are intended for travel over generally flat terrain, they are optimized for light weight and efficiency of motion.

Boots intended for more cross country travel generally have a lower cuff, softer flex and lighter weight.

Downhill techniques, alpine, telemark and snowboarding, all perform turns by rotating the ski or board onto its edge.

Snowboard boots and bindings are normally far simpler than their downhill counterparts, rarely including release systems for instance, and need to provide mechanical support only in the fore and aft directions.

These typically consist of an external frame, generally L-shaped, which the snowboarder steps into and then fastens down using straps over the boot.