Slaughter-House Cases

Seeking to improve sanitary conditions, the Louisiana legislature and the city of New Orleans had established a corporation charged with regulating the slaughterhouse industry.

One writer described New Orleans in the mid-nineteenth century as plagued by "intestines and portions of putrefied animal matter lodged [around the drinking pipes]" whenever the tide from the Mississippi River was low; the offal came from the city's slaughterhouses.

[1] Animal entrails (known as offal), dung, blood, and urine contaminated New Orleans's drinking water, which was implicated in cholera and yellow fever outbreaks among the population.

[2] At the time, New York City, San Francisco, Boston, Milwaukee, and Philadelphia had similar provisions to confine butchers' establishments to particular areas in order to keep offal from contaminating the water supply.

The butchers based their claims on the due process, privileges or immunities, and equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment, which had been ratified by the states five years earlier.

It had been passed with the intention of protecting the civil rights of the millions of newly emancipated freedmen in the South, who had been granted citizenship in the United States.

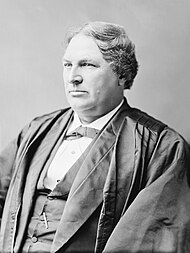

The butchers' attorney, former Supreme Court Justice John Archibald Campbell, who had retired from the federal bench because of his Confederate loyalties, represented persons in a number of cases in New Orleans to obstruct Radical Reconstruction.

On April 14, 1873, the Supreme Court issued a 5–4 decision in favor of the slaughterhouse company upholding the constitutionality of Louisiana's use of its police powers to regulate butchers.

[4] [O]n the most casual examination of the language of these amendments, no one can fail to be impressed with the one pervading purpose found in them all, lying at the foundation of each, and without which none of them would have been even suggested; we mean the freedom of the slave race, the security and firm establishment of that freedom, and the protection of the newly made freeman and citizen from the oppressions of those who had formerly exercised unlimited dominion over him.With this view of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments' purposes, the Court interpreted their protections very narrowly.

Field protested that Miller's narrow reading of the Fourteenth Amendment rendered it "a vain and idle enactment, which accomplished nothing and most unnecessarily excited Congress and the people on its passage".

[17] Field accepted Campbell's reading of the amendment as not confined to protection of freed slaves but embracing the common law presumption in favor of an individual right to pursue a legitimate occupation.

"[19] Justice Noah H. Swayne's dissent criticized the Court's rejection of the notion that the Fourteenth Amendment and its Privileges or Immunities Clause had been intended to transform American government.

It is necessary to enable the government of the nation to secure to everyone within its jurisdiction the rights and privileges enumerated, which, according to the plainest considerations of reason and justice and the fundamental principles of the social compact, all are entitled to enjoy.

"[24] In 2001, the American legal scholar Akhil Reed Amar wrote of the Slaughter-House Cases: "Virtually no serious modern scholar—left, right, and center—thinks that the decision is a plausible reading of the [Fourteenth] Amendment.

"[25] This view was echoed by historian Eric Foner, who wrote "[T]he Court's ... studied distinction between the privileges deriving from state and national citizenship should have been seriously doubted by anyone who read the Congressional debates of the 1860s".