Slave Narrative Collection

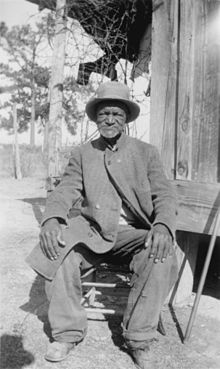

This resulted in several efforts to record the remembrances of living former enslaved individuals, especially as the survivors of the generation born into slavery before Emancipation in 1865 were declining in number.

In 1934 Lawrence D. Reddick, one of Johnson's students, proposed a federally-funded project to collect narratives from formerly enslaved individuals through the Federal Emergency Relief Administration, which was providing work opportunities for unemployed people as part of the first wave of New Deal funding.

Carolyn Dillard, director of the Georgia branch of the Writers' Project, pursued the goal of collecting stories from persons in the state who had been born into slavery.

[5] Historian Lauren Tilton asserts that "the Ex-Slave Narratives became a site to negotiate black people's right to full citizenship and to be a part of the nation's identity.

The subjectivity of the interviewer, the questions posed, responses from the interviewees, and the ways the stories were written shaped the narratives, which became a contested space to assert or de-legitimize black selfhood and therefore rights to full incorporation into the nation.

For instance, one historian has examined responses to conflict among the members of the Gullah community of the Low Country, with a view to relating it to traditional African ideas about restorative justice.

[11] However, large numbers of the narratives were not published until the 1970s, following the civil rights movement when changing culture created more widespread interest in early African American history.

The influence of New Social History, as well as increased attention to the historical agency of enslaved individuals, led to new interpretations and analysis of slave life.

[13] As presented on the Henry Louis Gates Jr. series African-American Lives, the actor Morgan Freeman's great-grandmother Cindy Anderson was one of the people interviewed for the Slaves Narrative Project.