Slovak Republic (1939–1945)

Internal opposition to the fascist government's policies culminated in the Slovak National Uprising in 1944, itself triggered by the Nazi German occupation of the country.

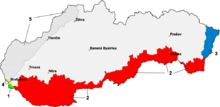

[11][12] After the Munich Agreement, Slovakia gained autonomy inside Czecho-Slovakia (as former Czechoslovakia had been renamed) and lost its southern territories to Hungary under the First Vienna Award.

On 13 March 1939, Hitler invited Monsignor Jozef Tiso (the Slovak ex-prime minister who had been deposed by Czechoslovak troops several days earlier) to Berlin and urged him to proclaim Slovakia's independence.

Hitler added that if Tiso had not consented, he would have allowed events in Slovakia to take place effectively, leaving it to the mercies of Hungary and Poland.

Britain and France refused to do so; in March 1939, both powers sent diplomatic notes to Berlin protesting developments in former Czechoslovakia as a breach of the Munich agreement and pledged not to acknowledge the territorial changes.

However, in September 1939, the USSR recognized Slovakia, admitted a Slovak representative, and closed the hitherto operational Czechoslovak legation in Moscow.

Shortly after the signing of the Tripartite Pact, Slovakia, following the Hungarian lead, sent messages of "spiritual adherence" to Germany and Italy.

[23] The state's most difficult foreign policy problem involved relations with Hungary, which had annexed one-third of Slovakia's territory by the First Vienna Award of 2 November 1938.

The government issued many antisemitic laws prohibiting the Jews from participation in public life and later supported their deportation to concentration camps erected by Germany on occupied Polish territory.

[26] Slovakia's pro-natalist programs limited access to previously available birth-control methods and introduced harsher punishments for already criminalized abortions.

[28] Pancke recommended that action should be taken to fuse the racially valuable part of the Slovaks into the German minority and remove the Romani and Jewish populations.

Yet, immediately after the break-up of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the creation of Czechoslovakia, Tiso transformed himself into a Slovak nationalist and career politician.

Tiso not only supported Nazi Germany's invasion of Poland in September 1939, but also contributed Slovak troops, which the Germans rewarded by allowing Slovakia to annex 300 square miles of Polish territory.

The second group was a mobile formation that consisted of two battalions of combined cavalry and motorcycle recon troops along with nine motorized artillery batteries, all commanded by Gustav Malár.

The two combat groups fought while pushing through the Nowy Sącz and Dukla Mountain Passes, advancing towards Dębica and Tarnów in the region of southern Poland.

In June 1944, the remnant of the division, no longer considered fit for combat due to low morale, was disarmed, and the personnel were assigned to construction work.

Hlinka guardsmen wore black uniforms and a cap shaped like a boat, with a woolen pompom on top, and they used the raised-arm salute.

At this point many of the guardsmen who were of middle-class origin quit, and thenceforth the organization consisted of peasants and unskilled laborers, together with various doubtful elements.

Soon after independence and along with the mass exile and deportation of Czechs, the Slovak Republic began a series of measures aimed against the Jews in the country.

Resembling the Nuremberg Laws, the code required Jews to wear a yellow armband and banned them from intermarriage and many jobs.

The initial terms were for "20,000 young, strong Jews", but the Slovak government quickly agreed to a German proposal to deport the entire population for "evacuation to territories in the East" meaning to Auschwitz-Birkenau.

[37] The deportations of Jews from Slovakia started on 25 March 1942 but halted on 20 October 1942 after a group of Jewish citizens, led by Gisi Fleischmann and Rabbi Michael Ber Weissmandl, built a coalition of concerned officials from the Vatican and the government, and, through a mix of bribery and negotiation, was able to stop the process.

It was launched on 29 August 1944 from Banská Bystrica to resist German troops that had occupied Slovak territory and to overthrow the collaborationist government of Jozef Tiso.

In retaliation, Einsatzgruppe H and the Hlinka Guard Emergency Divisions executed many Slovaks suspected of aiding the rebels as well as Jews who had avoided deportation until then, and destroyed 93 villages on suspicion of collaboration.

The First Slovak Republic ceased to exist de facto on 4 April 1945 when the Soviet Red Army 2nd Ukrainian Front captured Bratislava during the Bratislava–Brno offensive and occupied all of Slovakia.

[41][42] De jure it ceased to exist when the exiled Slovak government capitulated to General Walton Walker leading the XX Corps of the 3rd US Army on 8 May 1945 in the Austrian town of Kremsmünster.

At the end of the war, Vojtech Tuka suffered a stroke which confined him to a wheelchair; he emigrated together with his wife, nursing attendants, and personal doctor to Austria, where he was arrested by Allied troops following the capitulation of Germany and handed over to the officials of the renewed Czechoslovakia.

Decades later, after a DNA test in April 2008 that confirmed it, the body of Tiso was exhumed and buried in St Emmeram's Cathedral in Nitra, in accordance with canon law.

Ultranationalist propaganda proclaims Tiso as a "martyr" who "sacrificed his life for his belief and nation" and so tries to paint him as an innocent victim of communism and a saint.

[51] The Shop on Main Street is a 1965 Czechoslovakian film[52] about the Aryanization program during World War II in the Slovak Republic.