Slow sand filter

They are typically 1–2 m (3.3–6.6 ft) deep, can be rectangular or cylindrical in cross section and are used primarily to treat surface water.

The sand itself does not perform any filtration function but simply acts as a substrate, unlike its counterparts for ultraviolet and pressurized treatments.

[3][4] This installation provided filtered water for every resident of the area, and the network design was widely copied throughout the United Kingdom in the ensuing decades.

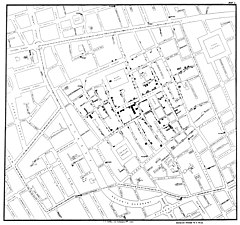

The practice of water treatment soon became mainstream, and the virtues of the system were made starkly apparent after the investigations of the physician John Snow during the 1854 Broad Street cholera outbreak.

Water treatment came to the United States in 1872 when Poughkeepsie, New York, opened the first slow sand filtration plant,[7] dramatically reducing instances of cholera and typhoid fever which had been seriously impacting the local community.

The Schmutzdecke is formed in the first 10–20 days of operation[9] and consists of bacteria, fungi, protozoa, rotifera and a range of aquatic insect larvae.

As an epigeal biofilm ages, more algae tend to develop and larger aquatic organisms may be present including some bryozoa, snails and Annelid worms.

As water passes through the hypogeal layer, particles of foreign matter are trapped in the mucilaginous matrix and soluble organic material is adsorbed.

The water produced from an exemplary slow sand filter is of excellent quality with 90–99% bacterial cell count reduction.