Lingchi

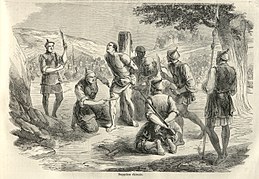

In this form of execution, a knife was used to methodically remove portions of the body over an extended period of time, eventually resulting in death.

[citation needed] In addition, to be cut to pieces meant that the body of the victim would not be "whole" in spiritual life after death.

[5][6] [7][8] [9][10][11][12] While it is difficult to obtain accurate details of how the executions took place, they generally consisted of cuts to the arms, legs, and chest leading to amputation of limbs, followed by decapitation or a stab to the heart.

Art historian James Elkins argues that extant photos of the execution clearly show that the "death by division" (as it was termed by German criminologist Robert Heindl) involved some degree of dismemberment while the subject was living.

[13] Elkins also argues that, contrary to the apocryphal version of "death by a thousand cuts", the actual process could not have lasted long.

[citation needed] John Morris Roberts, in Twentieth Century: The History of the World, 1901 to 2000 (2000), writes "the traditional punishment of death by slicing ... became part of the western image of Chinese backwardness as the 'death of a thousand cuts'."

Roberts then notes that slicing "was ordered, in fact, for K'ang Yu-Wei, a man termed the 'Rousseau of China', and a major advocate of intellectual and government reform in the 1890s".

[29] Although officially outlawed by the government of the Qing dynasty in 1905,[30] lingchi became a widespread Western symbol of the Chinese penal system from the 1910s on, and in Zhao Erfeng's administration.

Another early proposal for abolishing lingchi was submitted by Lu You (1125–1210) in a memorandum to the imperial court of the Southern Song dynasty.

Lu You there stated, "When the muscles of the flesh are already taken away, the breath of life is not yet cut off, liver and heart are still connected, seeing and hearing still exist.

[45][failed verification] Reports from Qing dynasty jurists such as Shen Jiaben show that executioners' customs varied, as the regular way to perform this penalty was not specified in detail in the penal code.

[citation needed] Lingchi was also known in Vietnam, notably being used as the method of execution of the French missionary Joseph Marchand, in 1835, as part of the repression following the unsuccessful Lê Văn Khôi revolt.

An 1858 account by Harper's Weekly claimed the martyr Auguste Chapdelaine was also killed by lingchi but in China; in reality he was beaten to death.

The tenth song on Taylor Swift's seventh album, Lover, is entitled "Death By A Thousand Cuts" and compares the singer's heartbreak to this punishment.

Agustina Bazterrica mentioned the torture in her book Tender is the Flesh, as the method used by the sister of the protagonist to make the meat served at the memorial party fresh and tasty.

Inspired by the 1905 photos, Chinese artist Chen Chieh-jen created a 25-minute, 2002 video called Lingchi – Echoes of a Historical Photograph, which has generated some controversy.

[68] The 2007 film The Warlords, which is loosely based on historical events during the Taiping Rebellion, ended with one of its main characters executed by Lingchi.