Shape-memory alloy

Parts made of shape-memory alloys can be lightweight, solid-state alternatives to conventional actuators such as hydraulic, pneumatic, and motor-based systems.

[8] The shape memory effect (SME)[9] occurs because a temperature-induced phase transformation reverses deformation, as shown in the previous hysteresis curve.

When a shape-memory alloy is in its cold state (below Mf), the metal can be bent or stretched and will hold those shapes until heated above the transition temperature.

If large stresses are applied, plastic behavior such as detwinning and slip of the martensite will initiate at sites such as grain boundaries or inclusions.

[21][22] This hysteresis loop shows the work done for each cycle of the material between states of small and large deformations, which is important for many applications.

Interfaces and inclusions will provide general sites for the transformation to begin, and if these are great in number, it will increase the driving force for nucleation.

One can see that as you increase the operational temperature of the SMA, σms will be greater than the yield strength, σy, and superelasticity will no longer be observable.

Greninger and Mooradian (1938) observed the formation and disappearance of a martensitic phase by decreasing and increasing the temperature of a Cu-Zn alloy.

The basic phenomenon of the memory effect governed by the thermoelastic behavior of the martensite phase was widely reported a decade later by Kurdjumov and Khandros (1949) and also by Chang and Read (1951).

One of the associate technical directors, Dr. David S. Muzzey, decided to see what would happen if the sample was subjected to heat and held his pipe lighter underneath it.

[25][26] There is another type of SMA, called a ferromagnetic shape-memory alloy (FSMA), that changes shape under strong magnetic fields.

The special property that allows shape-memory alloys to revert to their original shape after heating is that their crystal transformation is fully reversible.

SMAs are also subject to functional fatigue, a failure mode not typical of most engineering materials, whereby the SMA does not fail structurally but loses its shape-memory/superelastic characteristics over time.

As a result of cyclic loading (both mechanical and thermal), the material loses its ability to undergo a reversible phase transformation.

Boeing, General Electric Aircraft Engines, Goodrich Corporation, NASA, Texas A&M University and All Nippon Airways developed the Variable Geometry Chevron using a NiTi SMA.

Such a variable area fan nozzle (VAFN) design would allow for quieter and more efficient jet engines in the future.

These materials show promise for reducing the high vibration loads on payloads during launch as well as on fan blades in commercial jet engines, allowing for more lightweight and efficient designs.

[36] There is also strong interest in using SMAs for a variety of actuator applications in commercial jet engines, which would significantly reduce their weight and boost efficiency.

[37] Further research needs to be conducted in this area, however, to increase the transformation temperatures and improve the mechanical properties of these materials before they can be successfully implemented.

A review of recent advances in high-temperature shape-memory alloys (HTSMAs) is presented by Ma et al.[21] A variety of wing-morphing technologies are also being explored.

[35] The first high-volume product (> 5Mio actuators / year) is an automotive valve used to control low pressure pneumatic bladders in a car seat that adjust the contour of the lumbar support / bolsters.

Several smartphone companies have released handsets with optical image stabilisation (OIS) modules incorporating SMA actuators, manufactured under licence from Cambridge Mechatronics.

The late 1980s saw the commercial introduction of Nitinol as an enabling technology in a number of minimally invasive endovascular medical applications.

Memory metal has been utilized in orthopedic surgery as a fixation-compression device for osteotomies, typically for lower extremity procedures.

One example is the prevalence of dental braces using SMA technology to exert constant tooth-moving forces on the teeth; the nitinol archwire was developed in 1972 by orthodontist George Andreasen.

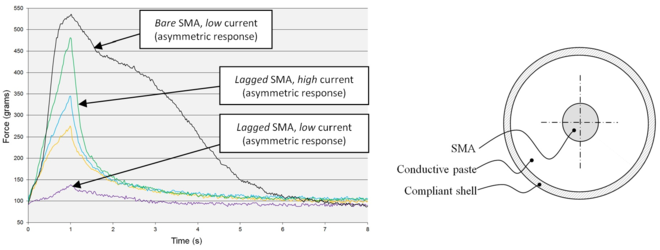

Traditional active cancellation techniques for tremor reduction use electrical, hydraulic, or pneumatic systems to actuate an object in the direction opposite to the disturbance.

SMAs have proven to be an effective method of actuation in hand-held applications, and have enabled a new class active tremor cancellation devices.

German scientists at Saarland University have produced a prototype machine that transfers heat using a nickel-titanium ("nitinol") alloy wire wrapped around a rotating cylinder.

If the new technology, which uses no refrigerants, proves economical and practical, it might offer a significant breakthrough in the effort to reduce climate change.

[citation needed] Shape memory alloys (SMAs), such as nickel-titanium (Nitinol), are used in clamping systems due to their unique thermo-responsive behavior.

- Cooling from austenite to (twinned) martensite, which happens either at beginning of the SMA’s lifetime or at the end of a thermal cycle.

- Applying a stress to detwin the martensite.

- Heating the martensite to reform austenite, restoring the original shape.

- Cooling the austenite back to twinned martensite.