Snorri Sturluson

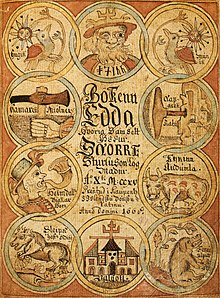

He is commonly thought to have authored or compiled portions of the Prose Edda, which is a major source for what is today known about Norse mythology and alliterative verse, and Heimskringla, a history of the Norse kings that begins with legendary material in Ynglinga saga and moves through to early medieval Scandinavian history.

[4] Snorri Sturluson was born in Hvammur í Dölum [is] (commonly transliterated as Hvamm or Hvammr)[5] as a member of the wealthy and powerful Sturlungar clan of the Icelandic Commonwealth, in AD 1179.

[citation needed] Snorri was raised from the age of three or four by Jón Loftsson, a relative of the Norwegian royal family, in Oddi, Iceland.

Key to his political and cultural education was his fosterage at Oddi, which resulted from a settlement regarding his father's legal dealings.

[8] The resulting settlement would have beggared Páll, but Jón Loftsson intervened in the Althing to mitigate the judgment and, to compensate Sturla, offered to raise and educate Snorri.

[citation needed] He was educated by Sæmundr fróði, grandfather of Jón Loftsson, at Oddi, and never returned to his parents' home.

[citation needed] In 1215, he became lawspeaker of the Althing, the only public office of the Icelandic commonwealth and a position of high respect.

In the summer of 1219, he met his Swedish colleague, the lawspeaker Eskil Magnusson, and his wife, Kristina Nilsdotter Blake, in Skara.

The Norwegian regents, however, cultivated Snorri, made him a skutilsvein, a senior title roughly equivalent to knight, and received an oath of loyalty.

The king hoped to extend his realm to Iceland, which he could do by a resolution of the Althing, where Snorri exerted much influence due to his political ties and legal acumen.

[citation needed] In 1220, Snorri returned to Iceland and by 1222 was back as law speaker of the Althing, which he held this time until 1232.

In 1224, Snorri married Hallveig Ormsdottir (c. 1199–1241), a granddaughter of Jón Loftsson, now a widow of great means with two young sons, and made a contract of joint property ownership (or helmingafélag) with her.

Snorri raised an armed party under his nephew Böðvar Þórðarson, and another under his son Órækja, with the intent of executing a first strike against his brother Sighvatur and Sturla Sighvatsson.

It is possible that Snorri perceived that only resolute, saga-like actions could achieve his objective, but if so he proved unwilling or incapable of carrying them out.

Haakon IV made an effort to intervene from afar, inviting all of Iceland's chieftains to a peace conference in Norway.

The reign of Haakon IV (Hákon Hákonarson), King of Norway, was troubled by civil war relating to questions of succession and was at various times divided into quasi-independent regions under rival contenders.

[citation needed] When Snorri arrived in Norway for the second time, it was clear to the king that he was no longer a reliable agent.

[citation needed] Snorri must have had his own ideas about the king's position and the validity of his orders, but at any rate he chose to disobey them; his words according to Sturlunga saga, 'út vil ek' (literally 'out want I', but idiomatically 'I will go home'), have become proverbial in Icelandic.

Meanwhile, Snorri resumed his chieftainship and made a bid to crush Gissur by prosecuting him in court for the deaths of his brother Sighvatr and nephew Sturla.

After the jarl's defeat, Haakon sent two agents to Gissur bearing a secret letter with orders to kill or capture Snorri.

[17] Snorri is considered a figure of enduring importance in this regard,[18] Halvdan Koht describing his work as "surpassing anything else that the Middle Ages have left us of historical literature".

To serve such views, Snorri and other leading Icelanders of his time are sometimes judged with an element of presentism, drawing on concepts that came into vogue only centuries later, such as state, independence, sovereignty, and nation.

[22] Jorge Luis Borges and María Kodama studied and translated the Gylfaginning to Spanish, providing a biographic account of Snorri at the prologue.