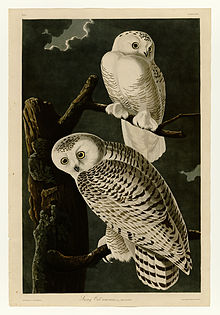

Snowy owl

[2][13] While the causes are not well understood, numerous, complex environmental factors often correlated with global warming are probably at the forefront of the fragility of the snowy owl's existence.

[2][8] The snowy owl was one of the many bird species originally described by Carl Linnaeus in his landmark 1758 10th edition of Systema Naturae, where it was given the binomial name Strix scandiaca.

[32] There are no subspecific or other geographical variations reported in the modern snowy owls, with individuals of vastly different origins breeding together readily due to their nomadic habits.

[5][8] Due in no small part to the difficulty and hazardousness of observation for biologists during these harsh times, there is very limited data on overwintering snowy owls in the tundra, including how many occur, where they winter and what their ecology is at this season.

[2][6][8][42] In North America, they occasionally regularly winter in the Aleutian island chain and do so broadly and with a fair amount of consistency in much of southern Canada, from British Columbia to Labrador.

[6] It has been interpreted from the morphology of their skeletal structure (i.e. their short, broad legs) that snowy owls are not well-suited to perching extensively in trees or rocks and prefer a flat surface to sit upon.

[5] However, they may perch more so in winter though do so only mainly when hunting, at times on hummocks, fenceposts, telegraph poles by roads, radio and transmission towers, haystacks, chimneys and the roofs of houses and large buildings.

[6] Strong stomach juices digest the flesh, while the indigestible bones, teeth, fur, and feathers are compacted into oval pellets that the bird regurgitates 18 to 24 hours after feeding.

[106][171] When historically breeding on Fetlar in Shetland, the main prey for snowy owls was European rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus), Eurasian oystercatcher (Haematopus ostralegus), parasitic jaegers (Stercorarius parasiticus) and Eurasian whimbrel (Numenius phaeopus), in roughly that order, followed by other bird species with most (rabbits and secondary birds) prey taken as adults but for the oystercatchers and jaegers which were taken largely as fully grown but only recently fledged juveniles.

[184] A different study of this area also showed the predominance of ducks and other water birds to wintering snowy owls here, although Townsend's vole (Microtus townsendii ) (10.65%) and snowshoe hare (Lepus americanus) (5.7%) were also notably in a sample of 122 prey items.

Richardson's ground squirrels (Urocitellus richardsonii) were consumed heavily in the Alberta study in a brief converged times of hibernation emergence and overwintering snowy owls.

[187] Snowy owls found in Michigan took meadow voles for 86% of the diet, white-footed mouse (Peromyscus leucopus) for 10.3% and northern short-tailed shrew (Blarina brevicauda) for 3.2%.

[140] Introduced common pheasants were found to be somewhat more vulnerable than native American gamebirds like ruffed grouse due to their tendency to crouch rather than flush when approached by a flighted predator like the snowy owl in a glade or field.

[191] The main subspecies of wood mouse was similarly dominant in the diet within County Mayo, Ireland and were presumably snatched at night due to their strict nocturnality.

On the Kuril Islands, wintering snowy owls' main foods were reported as tundra voles, brown rats, ermines, and whimbrel, in roughly that order.

Data from the Logan Airport in over 6,000 pellets shows that meadow vole and brown rats predominated the diet in the area, supplanted by assorted birds both small and large.

[8][195] Additionally, other birds as large as western capercaillie (Tetrao urogallus) (of both sexes), greater sage-grouse (Centrocercus urophasianus), yellow-billed loons (Gavia adamsii) and cygnets of Bewick's swans (Cygnus columbianus bewickii) can be taken by snowy owl.

In sometimes differing parts of the Arctic, competing predators for lemmings are, in addition to short-eared owls, pomarine jaegers (Stercorarius pomarinus), long-tailed jaegers (Stercorarius longicaudus), rough-legged buzzards (Buteo lagopus), hen harriers (Circus cyaenus), northern harriers (Circus hudsonius) and generally less specialized gyrfalcons (Falco rusticollis), peregrine falcons (Falco peregrinus), glaucous gulls (Larus hypoboreus) and common ravens (Corvus corax).

[205][206] When unusually breeding south in the Subarctic such as western Alaska, Scandinavia and central Russia, the number of predators with which the snowy owls are obligated to share prey and compete with may be too numerous to name.

[7] 9 radio-tagged female snowy owls about Bylot Island were tracked to study how pre-laying snow cover affects their searching behavior for breeding areas.

[6] While courting, the male often also carries a lemming in his bill, then bows with cocked tail, similarly as in related owls (seldom displaying some other prey like snow buntings).

[6] Females in breeding season often develop a very extensive brood patch which in this species is a fairly enormous, high vascularized featherless area of pink belly skin.

[8] At times, humans are forcefully dive-bombed upon, while other potential threats are dealt with in a “forward-threat” where the male walks towards the intruders, engaging in impressive feather-raising and fanning out of half-spread wings until they run forward and slash with both their feet and bill.

[7][12][79][77][64] Fairly serious injuries have been sustained in the worst of snowy owl defensive attacks, including cranial trauma, requiring researchers to make the long trek back to medical care, although human fatalities are not known.

[231] In other instances, distraction displays are engaged in against predators, with a "broken-wing act" including high, thin squeals interspersed with weird squeaks, often taking flight only to quickly fall from the sky and imitate a struggle.

[238] It is often reputed that snowy owls frequently died from starvation, with historical accounts opining that they "had to" leave their breeding grounds due to lemming "crashes" but would starve to the south.

[8] Of 71 dead snowy owls found in winter in the northern Great Plains, 86% died from assorted traumas, including collisions with automobiles and other, usually manmade, objects as well as electrocutions and shootings.

[219] In Norway, potential sources of disturbance near the nests include tourism, recreation, reindeer husbandry, motorized traffic, dogs, photographers, ornithologists and scientists.

[268] While the species was once otherwise killed as food and then later shot out of resentment for perceived threats against domestic and favored game stock, the reasoning behind ongoing shooting of snowy owls into the 21st century is not well-understood.

These and potentially many other issues (possibly including modifying migrating behavior, vegetation composition, increased insect, disease and parasite activities, risk of hyperthermia) are a matter of concern.