Social anthropology

; see key concepts of cognitive anthropology) are the product of biological and cultural factors that manifest in individual brain development, neural wiring, and neurochemical homeostasis.

[16] According to received view in neuroscience, an observed human behavior, in any context, is the last event in a long chain of biological and cultural interactions.

It is differentiated from sociology, both in its main methods (based on long-term participant observation and linguistic competence),[21] and in its commitment to the relevance and illumination provided by micro studies.

[22] Many social anthropologists use quantitative methods, too, particularly those whose research touches on topics such as local economies, demography, human ecology, cognition, or health and illness.

[23] More recent and currently specializations are: The subject has been enlivened by, and has contributed to, approaches from other disciplines, such as philosophy (ethics, phenomenology, logic), the history of science, psychoanalysis, and linguistics.

Social anthropology has historical roots in a number of 19th-century disciplines, including the study of Classics, ethnography, ethnology, folklore, linguistics, and sociology, among others.

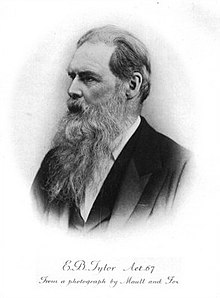

Its immediate precursor took shape in the work of Edward Burnett Tylor and James George Frazer in the late 19th century and underwent major changes in both method and theory during the period 1890–1920 with a new emphasis on original fieldwork, long-term holistic study of social behavior in natural settings, and the introduction of French and German social theory.

Such exhibitions were attempts to illustrate and prove in the same movement the validity of scientific racism, whose first formulation may be found in Arthur de Gobineau's An Essay on the Inequality of Human Races (1853–1855).

In 1931, the Colonial Exhibition in Paris still displayed Kanaks from New Caledonia in the "indigenous village"; it received 24 million visitors in six months, thus demonstrating the popularity of such "human zoos".

Edward Burnett Tylor (1832–1917) and James George Frazer (1854–1941) are generally considered the antecedents to modern social anthropologists in Great Britain.

Although the British anthropologist Tylor undertook a field trip to Mexico, both he and Frazer derived most of the material for their comparative studies through extensive reading, not fieldwork, mainly the Classics (literature and history of Ancient Greece and Rome), the work of the early European folklorists, and reports from missionaries, travelers, and contemporaneous ethnologists.

"[33] Tylor formulated one of the early and influential anthropological conceptions of culture as "that complex whole, which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by [humans] as [members] of society.

Cambridge University financed a multidisciplinary expedition to the Torres Strait Islands in 1898, organized by Alfred Cort Haddon and including a physician-anthropologist, William Rivers, as well as a linguist, a botanist, and other specialists.

A decade and a half later, the Polish anthropology student Bronisław Malinowski (1884–1942) was beginning what he expected to be a brief period of fieldwork in the old model, collecting lists of cultural items, when the outbreak of the First World War stranded him in New Guinea.

Modern social anthropology was founded in Britain at the London School of Economics and Political Science following World War I. Influences include both the methodological revolution pioneered by Bronisław Malinowski's process-oriented fieldwork in the Trobriand Islands of Melanesia between 1915 and 1918[36] and Alfred Radcliffe-Brown's theoretical program for systematic comparison that was based on a conception of rigorous fieldwork and the structure-functionalist conception of Durkheim’s sociology.

[37][38] Other intellectual founders include W. H. R. Rivers and A. C. Haddon, whose orientation reflected the contemporary Parapsychologies of Wilhelm Wundt and Adolf Bastian, and Sir E. B. Tylor, who defined anthropology as a positivist science following Auguste Comte.

However, after reading the work of French sociologists Émile Durkheim and Marcel Mauss, Radcliffe-Brown published an account of his research (entitled simply The Andaman Islanders) that paid close attention to the meaning and purpose of rituals and myths.

Malinowski and Radcliffe-Brown's influence stemmed from the fact that they, like Boas, actively trained students and aggressively built up institutions that furthered their programmatic ambitions.

From the late 1930s until the postwar period appeared a string of monographs and edited volumes that cemented the paradigm of British Social Anthropology (BSA).

During this period Gluckman was also involved in a dispute with American anthropologist Paul Bohannan on ethnographic methodology within the anthropological study of law.