Sociobiology

It draws from disciplines including psychology, ethology, anthropology, evolution, zoology, archaeology, and population genetics.

Critics, led by Richard Lewontin and Stephen Jay Gould, argued that genes played a role in human behavior, but that traits such as aggressiveness could be explained by social environment rather than by biology.

[6] Sociobiology is based on the premise that some behaviors (social and individual) are at least partly inherited and can be affected by natural selection.

This behavior is adaptive because killing the cubs eliminates competition for their own offspring and causes the nursing females to come into heat faster, thus allowing more of his genes to enter into the population.

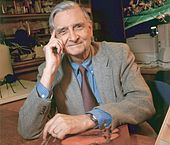

In 1956, E. O. Wilson came in contact with this emerging sociobiology through his PhD student Stuart A. Altmann, who had been in close relation with the participants to the 1948 conference.

Altmann developed his own brand of sociobiology to study the social behavior of rhesus macaques, using statistics, and was hired as a "sociobiologist" at the Yerkes Regional Primate Research Center in 1965.

The book pioneered and popularized the attempt to explain the evolutionary mechanics behind social behaviors such as altruism, aggression, and nurturance, primarily in ants (Wilson's own research specialty) and other Hymenoptera, but also in other animals.

[12] Edward H. Hagen writes in The Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology that sociobiology is, despite the public controversy regarding the applications to humans, "one of the scientific triumphs of the twentieth century."

"Sociobiology is now part of the core research and curriculum of virtually all biology departments, and it is a foundation of the work of almost all field biologists. "

Sociobiological research on nonhuman organisms has increased dramatically and continuously in the world's top scientific journals such as Nature and Science.

That inherited adaptive behaviors are present in nonhuman animal species has been multiply demonstrated by biologists, and it has become a foundation of evolutionary biology.

However, there is continued resistance by some researchers over the application of evolutionary models to humans, particularly from within the social sciences, where culture has long been assumed to be the predominant driver of behavior.

Sociobiologists reason that this protective behavior likely evolved over time because it helped the offspring of the individuals which had the characteristic to survive.

The social behavior is believed to have evolved in a fashion similar to other types of nonbehavioral adaptations, such as a coat of fur, or the sense of smell.

[14] The mechanisms responsible for group selection employ paradigms and population statistics borrowed from evolutionary game theory.

The researchers who carry out those studies are careful to point out that heritability does not constrain the influence that environmental or cultural factors may have on those traits.

[18] The evolutionary neuroandrogenic (ENA) theory, by sociologist/criminologist Lee Ellis, posits that female sexual selection has led to increased competitive behavior among men, sometimes resulting in criminality.

[19] The novelist Elias Canetti also has noted applications of sociobiological theory to cultural practices such as slavery and autocracy.

For example, the transcription factor FEV (aka Pet1), through its role in maintaining the serotonergic system in the brain, is required for normal aggressive and anxiety-like behavior.