Socrates

Furthermore, Xenophon was biased in his depiction of his former friend and teacher: he believed Socrates was treated unfairly by Athens, and sought to prove his point of view rather than to provide an impartial account.

[39] More recently, Charles H. Kahn has reinforced the skeptical stance on the unsolvable Socratic problem, suggesting that only Plato's Apology has any historical significance.

He learned the basic skills of reading and writing and, like most wealthy Athenians, received extra lessons in various other fields such as gymnastics, poetry and music.

As Plato describes in his Apology, Socrates and four others were summoned to the Tholos and told by representatives of the Thirty Tyrants (which began ruling in 404 BC) to arrest Leon for execution.

[51] Although Socrates was attracted to youth, as was common and accepted in ancient Greece, he resisted his passion for young men because, as Plato describes, he was more interested in educating their souls.

[61] Because of their tyrannical measures, some Athenians organized to overthrow the Tyrants—and, indeed, they managed to do so briefly—until a Spartan request for aid from the Thirty arrived and a compromise was sought.

[75] The case for it being a political persecution is usually challenged by the existence of an amnesty that was granted to Athenian citizens in 403 BC to prevent escalation to civil war after the fall of the Thirty.

[97] For example, during his trial, with his life at stake, Socrates says: "I thought Evenus a happy man, if he really possesses this art (technē), and teaches for so moderate a fee.

[100] One explanation is that Socrates is being either ironic or modest for pedagogical purposes: he aims to let his interlocutor to think for himself rather than guide him to a prefixed answer to his philosophical questions.

James H. Lesher has argued that Socrates claimed in various dialogues that one word is linked to one meaning (i.e. in Hippias Major, Meno, and Laches).

When Socrates first hears the details of the story, he comments, "It is not, I think, any random person who could do this [prosecute one's father] correctly, but surely one who is already far progressed in wisdom".

[115] Another line of thought holds that Socrates conceals his philosophical message with irony, making it accessible only to those who can separate the parts of his statements which are ironic from those which are not.

He also believed that humans were guided by the cognitive power to comprehend what they desire, while diminishing the role of impulses (a view termed motivational intellectualism).

[127] In Ancient Greece, organized religion was fragmented, celebrated in a number of festivals for specific gods, such as the City Dionysia, or in domestic rituals, and there were no sacred texts.

Religion intermingled with the daily life of citizens, who performed their personal religious duties mainly with sacrifices to various gods.

[128] Whether Socrates was a practicing man of religion or a 'provocateur atheist' has been a point of debate since ancient times; his trial included impiety accusations, and the controversy has not yet ceased.

[132] Socrates, in Euthyphro, reaches a conclusion which takes him far from the age's usual practice: he considers sacrifices to the gods to be useless, especially when they are driven by the hope of receiving a reward in return.

[147] In several texts (e.g., Plato's Euthyphro 3b5; Apology 31c–d; Xenophon's Memorabilia 1.1.2) Socrates claims he hears a daimōnic sign—an inner voice heard usually when he was about to make a mistake.

Socrates gave a brief description of this daimonion at his trial (Apology 31c–d): "...The reason for this is something you have heard me frequently mention in different places—namely, the fact that I experience something divine and daimonic, as Meletus has inscribed in his indictment, by way of mockery.

[163] Socrates spent his time conversing with citizens, among them powerful members of Athenian society, scrutinizing their beliefs and bringing the contradictions of their ideas to light.

While there is no clear textual evidence, one widely held theory holds that Socrates leaned towards democracy: he disobeyed the one order that the oligarchic government of the Thirty Tyrants gave him; he respected the laws and political system of Athens (which were formulated by democrats); and, according to this argument, his affinity for the ideals of democratic Athens was a reason why he did not want to escape prison and the death penalty.

[165] A less mainstream argument suggests that Socrates favoured democratic republicanism, a theory that prioritizes active participation in public life and concern for the city.

With the exception of the Epicureans and the Pyrrhonists, almost all philosophical currents after Socrates traced their roots to him: Plato's Academy, Aristotle's Lyceum, the Cynics, and the Stoics.

After leaving Athens and returning to his home city of Cyrene, he founded the Cyrenaic philosophical school which was based on hedonism, and endorsing living an easy life with physical pleasures.

The Stoics assigned virtue a crucial role in attaining happiness and also prioritized the relation between goodness and ethical excellence, all of which echoed Socratic thought.

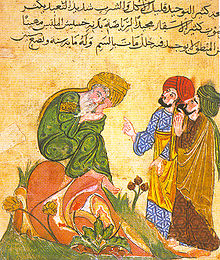

Plato's works on Socrates, as well as other ancient Greek literature, were translated into Arabic by early Muslim scholars such as Al-Kindi, Jabir ibn Hayyan, and the Muʿtazila.

Bruni and Manetti were interested in defending secularism as a non-sinful way of life; presenting a view of Socrates that was aligned with Christian morality assisted their cause.

[194] In early modern France, Socrates's image was dominated by features of his private life rather than his philosophical thought, in various novels and satirical plays.

[213] Continental philosophers Hannah Arendt, Leo Strauss and Karl Popper, after experiencing the horrors of World War II, amidst the rise of totalitarian regimes, saw Socrates as an icon of individual conscience.

He sees an elitist Socrates in Plato's Republic as exemplifying why the polis is not, and could not be, an ideal way of organizing life, since philosophical truths cannot be digested by the masses.