Albertus Soegijapranata

Known as a bright child, around 1909 he was asked by Father Frans van Lith to enter Xaverius College, a Jesuit school in Muntilan, where Soegija slowly became interested in Catholicism.

In 1928, he returned to the Netherlands to study theology at Maastricht, where he was ordained by Bishop of Roermond Laurentius Schrijnen on 15 August 1931; Soegija then added the word "pranata" to the back of his name.

The Empire of Japan invaded the Indies beginning in early 1942, and during the ensuing occupation numerous churches were seized and clergymen were arrested or killed.

Soegijapranata helped broker a ceasefire after a five-day battle between Japanese and Indonesian troops and called for the central government to send someone to deal with the unrest and food shortages in the city.

There, Karijosoedarmo began to serve as a courtier at the Kraton Ngayogyakarta Hadiningrat to Sultan Hamengkubuwono VII, while his wife sold fish;[1] despite this, the family was poor and sometimes had little food.

[1] Around 1909 he was asked by Father Frans van Lith to join the Jesuit school in Muntilan, 30 kilometres (19 mi) north-west of Yogyakarta.

Van Lith cited the works of Thomas Aquinas, while Mertens discussed the Trinity as explained by Augustine of Hippo; the latter told him that humans were not meant to understand God with their limited knowledge.

[15] On another occasion, a visit by a Capuchin missionary – who was physically quite different from the Jesuit teachers[c] – led Soegija to consider becoming a priest, an idea which his parents accepted.

Beginning in 1923 he studied philosophy at Berchmann College in Oudenbosch;[20] during this time he examined the teachings of Thomas Aquinas and began writing on Christianity.

He also translated some of the results of the 27th International Eucharistic Congress, held in Amsterdam in 1924, for the Javanese-language magazine Swaratama, which circulated mainly among Xaverius alumni.

[e][29] After his ordination, Soegija appended the word pranata, meaning "prayer" or "hope", as a suffix to his birth name;[13] such additions were a common practice in Javanese culture after its bearer reached an important milestone.

[31] That year he wrote an autobiography, entitled La Conversione di un Giavanese (The Conversion of a Javanese); the work was released in Italian, Dutch, and Spanish.

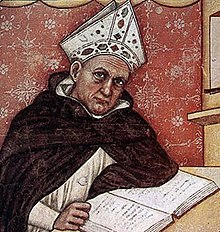

[f][35] Soegijapranata was, by this point, a short and chubby man with what the Dutch historian Geert Arend van Klinken described as "a boyish sense of humour that won him many friends".

After van Driessche's death in June 1934, Soegijapranata's duties were extended to include the village of Ganjuran, Bantul, 20 kilometres (12 mi) south of the city, which was home to more than a thousand native Catholics.

[46] On 1 August 1940 Willekens received a telegram from Pro-Secretary of State Giovanni Battista Montini ordering that Soegijapranata be put in charge of the newly established apostolic vicariate.

[54] The vicariate included Semarang, Yogyakarta, Surakarta, Kudus, Magelang, Salatiga, Pati, and Ambarawa; its geographic conditions ranged from the fertile lowlands of the Kedu Plain to the arid Gunung Sewu mountainous area.

"[h][61] The occupation government captured numerous (mostly Dutch) men and women, both clergy and laymen,[i] and instituted policies that changed how services were held.

[61] Soegijapranata attempted to resist these seizures, at times filling the locations with people to make them unmanageable or indicating that other buildings, such as cinemas, would serve Japanese needs better.

In support of the new Republic, Soegijapranata had an Indonesian flag flown in front of the Gedangan Rectory;[78] however, he did not formally recognise the nation's independence, owing to his correspondence with Willekens regarding the Church's neutrality.

Soegijapranata then contacted the Japanese and, that afternoon, brokered a cease-fire agreement in his office at Gedangan, despite Indonesian forces' firing at the Gurkha soldiers posted in front of the building.

[84] Military conflicts throughout the area and an ongoing Allied presence led to food shortages throughout the city, as well as constant blackouts and the establishment of a curfew.

In an attempt to deal with these issues, Soegijapranata sent a local man, Dwidjosewojo, to the capital at Jakarta – renamed from Batavia during the Japanese occupation – to speak with the central government.

[96] After the Dutch captured the capital during Operation Kraai on 19 December 1948, Soegijapranata ordered that the Christmas festivities be kept simple to represent the Indonesian people's suffering.

[3] The following year the Bishops' Conference of Indonesia (MAWI, later KWI), recognising Soegijapranata's devotion to the poor, put him in charge of establishing social-support programmes throughout the archipelago.

[104] On 2 November 1955, he and several other bishops issued a decree denouncing communism, Marxism, and materialism, and asking the government to ensure fair and equitable treatment for all citizens.

[58] When this happened, Soegijapranata was in Europe to attend the Second Vatican Council as part of the Central Preparatory Commission;[108] he was one of eleven diocesan bishops and archbishops from Asia.

[108][111] As Sukarno did not want Soegijapranata buried in the Netherlands, his body was flown to Indonesia after last rites were performed by Cardinal Bernardus Johannes Alfrink.

[116] Henricia Moeryantini, a nun in the Order of Carolus Borromeus, writes that the Catholic Church became nationally influential under Soegijapranata, and that the archbishop cared too much for the people to take an outsider's approach.

[117] Van Klinken writes that Soegijapranata eventually became like a priyayi, or Javanese nobleman, within the church, as "committed to hierarchy and the status quo as to the God who created them".

Starring Nirwan Dewanto in the titular role, the film followed Soegijapranata's activities during the 1940s, amidst a backdrop of the Japanese occupation and the war for Indonesian independence.