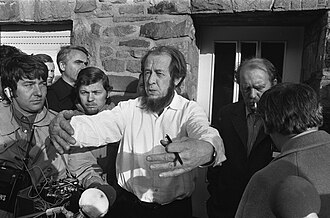

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

While serving as a captain in the Red Army during World War II, Solzhenitsyn was arrested by SMERSH and sentenced to eight years in the Gulag and then internal exile for criticizing Soviet leader Joseph Stalin in a private letter.

[19] A series of writings published late in his life, including the early uncompleted novel Love the Revolution!, chronicle his wartime experience and growing doubts about the moral foundations of the Soviet regime.

In this poem, which describes the gang-rape of a Polish woman whom the Red Army soldiers mistakenly thought to be a German,[22] the first-person narrator comments on the events with sarcasm and refers to the responsibility of official Soviet writers like Ilya Ehrenburg.

After the difficult cycles of such ponderings over many years, whenever I mentioned the heartlessness of our highest-ranking bureaucrats, the cruelty of our executioners, I remember myself in my Captain's shoulder boards and the forward march of my battery through East Prussia, enshrouded in fire, and I say: 'So were we any better?

'"[23] In February 1945, while serving in East Prussia, Solzhenitsyn was arrested by SMERSH for writing derogatory comments in private letters to a friend, Nikolai Vitkevich,[24] about the conduct of the war by Joseph Stalin, whom he called "Hozyain" ("the boss"), and "Balabos" (Yiddish rendering of Hebrew baal ha-bayit for "master of the house").

[30] The first part of Solzhenitsyn's sentence was served in several work camps; the "middle phase", as he later referred to it, was spent in a sharashka (a special scientific research facility run by Ministry of State Security), where he met Lev Kopelev, upon whom he based the character of Lev Rubin in his book The First Circle, published in a self-censored or "distorted" version in the West in 1968 (an English translation of the full version was eventually published by Harper Perennial in October 2009).

"[42] In her 1974 memoir, Sanya: My Life with Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, she wrote that she was "perplexed" that the West had accepted The Gulag Archipelago as "the solemn, ultimate truth", saying its significance had been "overestimated and wrongly appraised".

In his Nobel Prize acceptance speech he wrote that "during all the years until 1961, not only was I convinced I should never see a single line of mine in print in my lifetime, but, also, I scarcely dared allow any of my close acquaintances to read anything I had written because I feared this would become known.

The seizing of his novel manuscript first made him desperate and frightened, but gradually he realized that it had set him free from the pretenses and trappings of being an "officially acclaimed" writer, a status which had become familiar but which was becoming increasingly irrelevant.

After the KGB had confiscated Solzhenitsyn's materials in Moscow, in the years 1965 to 1967, the preparatory drafts of The Gulag Archipelago were turned into finished typescript in hiding at his friends' homes in Soviet Estonia.

"[54] Historian J. Arch Getty wrote of Solzhenitsyn's methodology that "such documentation is methodically unacceptable in other fields of history",[55] which gives priority to vague hearsay and leads towards selective bias.

He was given an honorary literary degree from Harvard University in 1978 and on 8 June 1978 he gave a commencement address, condemning, among other things, the press, the lack of spirituality and traditional values, and the anthropocentrism of Western culture.

[69] The KGB also sponsored a series of hostile books about Solzhenitsyn, most notably a "memoir published under the name of his first wife, Natalia Reshetovskaya, but probably mostly composed by Service A", according to historian Christopher Andrew.

KGB and CPSU experts finally concluded that he alienated American listeners by his "reactionary views and intransigent criticism of the US way of life", so no further active measures would be required.

[citation needed] Solzhenitsyn's warnings about the dangers of Communist aggression and the weakening of the moral fiber of the West were generally well received in Western conservative circles (e.g. Ford administration staffers Dick Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld advocated on Solzhenitsyn's behalf for him to speak directly to President Gerald Ford about the Soviet threat),[70] prior to and alongside the tougher foreign policy pursued by US President Ronald Reagan.

He sought refuge in a dreamy past, where, he believed, a united Slavic state (the Russian empire) built on Orthodox foundations had provided an ideological alternative to western individualistic liberalism.

Solzhenitsyn also attacked both the Tsar and the Patriarch for using excommunication, Siberian exile, imprisonment, torture, and even burning at the stake against the Old Believers, who rejected the liturgical changes which caused the Schism.

[citation needed] Solzhenitsyn also argued that the Dechristianization of Russian culture, which he considered most responsible for the Bolshevik Revolution, began in 1666, became much worse during the Reign of Tsar Peter the Great, and accelerated into an epidemic during The Enlightenment, the Romantic era, and the Silver Age.

[citation needed] Expanding upon this theme, Solzhenitsyn once declared, "Over a half century ago, while I was still a child, I recall hearing a number of old people offer the following explanation for the great disasters that had befallen Russia: 'Men have forgotten God; that's why all this has happened.'

But if I were asked today to formulate as concisely as possible the main cause of the ruinous revolution that swallowed up some 60 million of our people, I could not put it more accurately than to repeat: 'Men have forgotten God; that's why all this has happened.

'"[91] In an interview with Joseph Pearce, however, Solzhenitsyn commented, "[The Old Believers were] treated amazingly unjustly because some very insignificant, trifling differences in ritual which were promoted with poor judgment and without much sound basis.

"[95] In his 1974 essay "Repentance and Self-Limitation in the Life of Nations", Solzhenitsyn urged "Russian Gentiles" and Jews alike to take moral responsibility for the "renegades" from both communities who enthusiastically embraced atheism and Marxism–Leninism and participated in the Red Terror and many other acts of torture and mass murder following the October Revolution.

[106] He also downplayed the number of victims of an 1882 pogrom despite current evidence, and failed to mention the Beilis affair, a 1911 trial in Kiev where a Jew was accused of ritually murdering Christian children.

He commented that, while the French Reign of Terror ended with the Thermidorian reaction and the toppling of the Jacobins and the execution of Maximilien Robespierre, its Soviet equivalent continued to accelerate until the Khrushchev thaw of the 1950s.

"[115] Solzhenitsyn recalled: "I had to explain to the people of Spain in the most concise possible terms what it meant to have been subjugated by an ideology as we in the Soviet Union had been, and give the Spanish to understand what a terrible fate they escaped in 1939".

According to Peter Brooke, however, Solzhenitsyn in reality approached the position argued by Christian Dmitri Panin, with whom he had a fall out in exile, namely that evil "must be confronted by force, and the centralised, spiritually independent Roman Catholic Church is better placed to do it than Orthodoxy with its otherworldliness and tradition of subservience to the State.

[120] Regarding Ukraine he wrote “All the talk of a separate Ukrainian people existing since something like the ninth century and possessing its own non-Russian language is recently invented falsehood” and "we all sprang from precious Kiev".

[129] He considered the West to possess a blind sense of cultural superiority, and that this manifested itself as the belief that "vast regions everywhere on our planet should develop and mature to the level of present-day Western systems".

[136] In 2006, Solzhenitsyn accused NATO of trying to bring Russia under its control; he stated that this was visible because of its "ideological support for the 'colour revolutions' and the paradoxical forcing of North Atlantic interests on Central Asia".

[134] In a 2006 interview with Der Spiegel he stated "This was especially painful in the case of Ukraine, a country whose closeness to Russia is defined by literally millions of family ties among our peoples, relatives living on different sides of the national border.