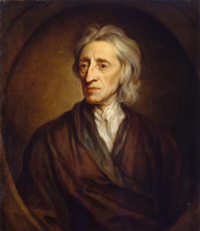

Some Thoughts Concerning Education

"[3] As England became increasingly mercantilist and secularist, the humanist educational values of the Renaissance, which had enshrined scholasticism, came to be regarded by many as irrelevant.

[4] Following in the intellectual tradition of Francis Bacon, who had challenged the cultural authority of the classics, reformers such as Locke, and later Philip Doddridge, argued against Cambridge and Oxford's decree that "all Bachelor and Undergraduates in their Disputations should lay aside their various Authors, such that caused many dissensions and strives in the Schools, and only follow Aristotle and those that defend him, and take their Questions from him, and that they exclude from the Schools all steril and inane Questions, disagreeing from the ancient and true Philosophy [sic].

[9] Although Locke revised and expanded the text five times before he died,[10] he never substantially altered the "familiar and friendly style of the work.

"[11] The "Preface" alerted the reader to its humble origins as a series of letters and, according to Nathan Tarcov, who has written an entire volume on Some Thoughts, advice that otherwise might have appeared "meddlesome" became welcome.

He defines virtue as a combination of self-denial and rationality: "that a man is able to deny himself his own desires, cross his own inclinations, and purely follow what reason directs as best, though the appetite lean the other way" (Locke's emphasis).

Throughout the Essay, Locke bemoans the irrationality of the majority and their inability, because of the authority of custom, to change or forfeit long-held beliefs.

[29] His attempt to solve this problem is not only to treat children as rational beings but also to create a disciplinary system founded on esteem and disgrace rather than on rewards and punishments.

[30] For Locke, rewards such as sweets and punishments such as beatings turn children into sensualists rather than rationalists; such sensations arouse passions rather than reason.

As he writes, the instructor "should remember that his business is not so much to teach [the child] all that is knowable, as to raise in him a love and esteem of knowledge; and to put him in the right way of knowing and improving himself.

He deplores the long hours wasted on learning Latin and argues that children should first be taught to speak and write well in their native language,[38] particularly recommending Aesop's Fables.

[40] Locke's curricular recommendations reflect the break from scholastic humanism and the emergence of a new kind of education—one emphasising not only science but also practical professional training.

[41] Locke's pedagogical suggestions marked the beginning of a new bourgeois ethos that would come to define Britain in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

[42] When Locke began writing the letters that would eventually become Some Thoughts on Education, he was addressing an aristocrat, but the final text appeals to a much wider audience.

One of Locke's conclusions in Some Thoughts Concerning Education is that he "think[s] a Prince, a Nobleman, and an ordinary Gentleman's Son, should have different Ways of Breeding.

This interpretation is supported by a letter he wrote to Mary Clarke in 1685 stating that "since therefore I acknowledge no difference of sex in your mind relating ... to truth, virtue and obedience, I think well to have no thing altered in it from what is [writ for the son].

"[52] Martin Simons states that Locke "suggested, both by implication and explicitly, that a boy's education should be along the lines already followed by some girls of the intelligent genteel classes.

"[53] Rather than sending boys to schools which would ignore their individual needs and teach them little of value, Locke argues that they should be taught at home as girls already were and "should learn useful and necessary crafts of the house and estate.

"[56] Although Locke's statement indicates that he places a greater value on female than male beauty, the fact that these opinions were never published allowed contemporary readers to draw their own conclusions regarding the "different treatments" required for girls and boys, if any.

According to James A. Secord, an eighteenth-century scholar, Newbery included Locke's educational advice to legitimise the new genre of children's literature.

In the years following the publication of Locke's work, Etienne Bonnot de Condillac and Claude Adrien Helvétius eagerly adopted the idea that people's minds were shaped through their experiences and thus through their education.

These lessons focused pupils' attention on a particular thing and encouraged them to use all of their senses to explore it and urged them to use precise words to describe it.

According to Cleverley and Phillips, the television show Sesame Street is also "based on Lockean assumptions—its aim has been to give underprivileged children, especially in the inner cities, the simple ideas and basic experiences that their environment normally does not provide.