Son cubano

The international presence of the son can be traced back to the 1930s when many bands toured Europe and North America, leading to ballroom adaptations of the genre such as the American rhumba.

Similarly, radio broadcasts of son became popular in West Africa and the Congos, leading to the development of hybrid genres such as Congolese rumba.

In the 1960s, New York's music scene prompted the rapid success of salsa, a combination of son and other Latin American styles primarily recorded by Puerto Ricans.

Generally, there is an explicit difference between styles that incorporate elements of the son partially or totally, as evidenced by the distinction between bolero soneado and bolero-son.

Historically, most musicologists have supported the hypothesis that the direct ancestors (or earliest forms) of the son appeared in Cuba's Oriente Province, particularly in mountainous regions such as Sierra Maestra.

[2] These early styles, which include changüí, nengón, kiribá and regina,[9] were developed by peasants, many of which were of Bantu origin, in contrast to the Afro-Cubans of the western side of the island, which primarily descended from West African slaves (Yoruba, Ewe, etc.).

[1] These forms flourished in the context of rural parties such as guateques, where bungas were known to perform; these groups consisted of singers and guitarists playing variants such as the tiple, bandurria and bandola.

[14] For this reason, some academics such as Radamés Giro and Jesús Gómez Cairo indicate that awareness of the son was widespread in the whole island, including Havana, before the actual expansion of the genre in the 1910s.

[15][16] Musicologist Peter Manuel proposed an alternative hypothesis according to which a great deal of the son's structure originated from the contradanza in Havana around the second half of the 19th century.

Such story was first mentioned by Cuban historian Joaquín José García in 1845, who "cited" a chronicle supposedly written by Hernando de la Parra in the 16th century.

Parra's story was picked up, recycled and expanded by various authors throughout the second half of the 19th century, perpetuating the idea that such song was the first example of the son genre.

Despite being given credence by some authors in the first half of the 20th century, including Fernando Ortiz, the Crónicas were repeatedly shown to be apocryphal in subsequent studies by Manuel Pérez Beato, José Juan Arrom, Max Henríquez Ureña and Alberto Muguercia.

[21] Ned Sublette states about another famous trovador and sonero: "As a child, Miguel Matamoros played danzones and sones on his harmonica to entertain the workers at a local cigar factory.

'"[22] A partial list of trovadores that recorded rumbas, guarachas and sones in Havana at the beginning of the 20th century included: Sindo Garay, Manuel Corona, María Teresa Vera, Alberto Villalón, José Castillo, Juan Cruz, Juan de la Cruz, Nano León, Román Martínez, as well as the duos of Floro and Zorrilla, Pablito and Luna, Zalazar and Oriche, and also Adolfo Colombo, who was not a trovador but a soloist at Teatro Alhambra.

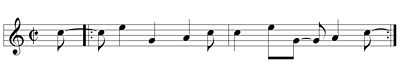

This group established the "classical" configuration of the son sextet composed of guitar, tres, bongos, claves, maracas and double bass.

[28] Popularization began in earnest with the arrival of radio broadcasting in 1922, which came at the same time as Havana's reputation as an attraction for Americans evading Prohibition laws.

A turning point that made this transformation possible occurred when then-president Machado publicly asked La Sonora Matancera to perform at his birthday party.

[29] At that time many sextets were founded such as Boloña, Agabama, Botón de Rosa and the famous Sexteto Occidente conducted by María Teresa Vera.

[32] They also occasionally included other instruments such as the bongo, and later they decided to expand the trio format to create a son conjunto by adding a piano, more guitars, tres and other voices.

In 1928, they travelled to New York with a recording contract by RCA Victor, and their first album caused such a great impact in the public that they soon became very famous at a national as well as an international level.

Original son conjuntos were faced with the options of either to disband and refocus on newer styles of Cuban music, or go back to their roots.

He used improvised solos, toques, congas, extra trumpets, percussion and pianos, although all these elements had been used previously ("Papauba", "Para bailar son montuno").

Beny Moré (known as El Bárbaro del Ritmo, "The Master of Rhythm") further evolved the genre, adding guaracha, bolero and mambo influences.

[35] During the 1940s and 1950s, the tourism boom in Cuba and the popularity of jazz and American music in general fostered the development of big bands and combos on the island.

These bands consisted of a relatively small horn section, piano, double bass, a full array of Cuban percussion instruments and a vocalist fronting the ensemble.

The commercialism of this new music movement led Cuban nightclub owners to recognize the revenue potential of hosting these types of bands to attract the growing flow of tourists.

The Buena Vista Social Club album and film as well as a stream of CDs triggered a worldwide Cuban music boom.

back : María Teresa Vera (guitar), Ignacio Piñeiro (double bass), Julio Torres Biart (tres); front : Miguelito Garcia (clave), Manuel Reinoso (bongo) and Francisco Sánchez (maracas)