Sources of Hamlet

A Scandinavian version of the story of Hamlet (called Amleth or Amlóði, which means "mad" or "not sane" in Old Norse) was put into writing around 1200 AD by Danish historian Saxo Grammaticus in his work Gesta Danorum (the first full history of Denmark).

Similar accounts are found in the Icelandic Saga of Hrolf Kraki and the Roman legend of Lucius Junius Brutus, both of which feature heroes who pretend to be insane in order to get revenge.

[4][5] Similarities include the prince's feigned madness, his accidental killing of the king's counsellor in his mother's bedroom, and the eventual slaying of his uncle.

The "hero as fool" story has many parallels (Roman, Spanish, Scandinavian and Arabic) and can be classified as a universal, or at least common Indo-European, narrative topos.

Its hero, Lucius ('shining, light'), changes his name and persona to Brutus ('dull, stupid'), playing the role to avoid the fate of his father and brothers, and eventually slaying his family's killer, King Tarquinius.

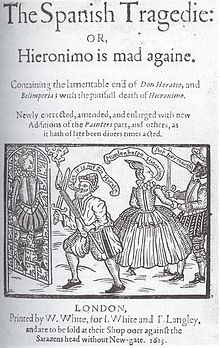

The upshot is that scholars cannot assert with any confidence how much material Shakespeare took from the Ur-Hamlet (if it even existed), how much from Belleforest or Saxo, and how much from other contemporary sources (such as Kyd's The Spanish Tragedy).

No clear evidence exists that Shakespeare made any direct references to Saxo's version (although its Latin text was widely available at the time).

For one, unlike Saxo and Belleforest, Shakespeare's play has no all-knowing narrator, thus inviting the audience to draw their own conclusions about the motives of its characters.

In 1869, George Russell French theorized that Hamlet's Polonius might have been inspired by William Cecil (Lord Burghley)—Lord High Treasurer and chief counsellor to Queen Elizabeth I.

[31] In 1963, A. L. Rowse said that Polonius's tedious verbosity might have resembled Burghley's,[32] and in 1964, Joel Hurstfield wrote that "[t]he governing classes were both paternalistic and patronizing; and nowhere is this attitude better displayed than in the advice which that archetype of elder statesmen William Cecil, Lord Burghley—Shakespeare's Polonius—prepared for his son".

[35] In 1921, Winstanley claimed "absolute" certainty that "the historical analogues exist; that they are important, numerous, detailed and undeniable" and that "Shakespeare is using a large element of contemporary history in Hamlet.

[37] Harold Jenkins criticised the idea of any direct personal satire as "unlikely" and "uncharacteristic of Shakespeare",[38] while G. R. Hibbard hypothesized that differences in names (Corambis/Polonius; Montano/Raynoldo) between the first quarto and subsequent editions might reflect a desire not to offend scholars at Oxford University, since Polonius was close to the Latin name for Robert Pullen, founder of Oxford University, and Reynaldo too close for safety to John Rainolds, the President of Corpus Christi College.

The author of the Ur-Hamlet, perhaps Shakespeare himself, seems to have been the first to drop the final H (originally indicating a Scandinavian TH-sound) and to attach an H to the front of the name.

[46] John Mackinnon Robertson, writing in 1897, suggested that the similarities in wording between Bruno's comedy Il Candelajo and Hamlet were completely commonplace for the time, and actually were within the text of "Ur-Hamlet" (above), rather than Shakespeare's later play: "drafted by a much lesser man than Shakespere.