South African Arms Deal

[5][6] Because of the financing arrangements and exchange rate fluctuations, the true cost of the contracts – only finally paid off in October 2020 – is estimated at far more, although the government's total expenditure on the package has never been disclosed.

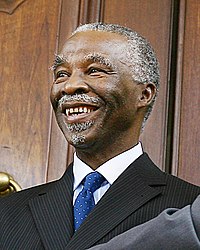

At least three former cabinet ministers – Joe Modise, Siphiwe Nyanda, and Stella Sigcau – and two former Presidents – Thabo Mbeki and Jacob Zuma – have been accused of improperly benefiting from the contracts.

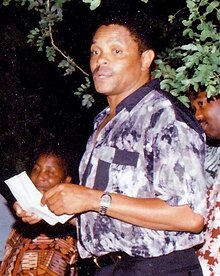

[5][10] The first post-apartheid Minister of Defence, Joe Modise, requested parliamentary approval for the acquisition of Spanish corvettes as early as 1994, but this was refused pending a threat assessment and strategic review of the country's broad military arrangements.

[13] The 1996 White Paper and 1998 Defence Review agreed, in line with the Constitution, that SANDF's primary function was to defend the territorial integrity and people of South Africa – in contrast to the posture of SADF, which towards the end of apartheid had been involved in internal political conflicts.

[5] The defence companies who supplied the equipment were paid between 2000 and 2014, while the South African government (through the National Treasury as debtor)[21] continued paying off related loans until October 2020.

[7] The major financiers of the package, some of whose loans were underwritten by their governments, were the following international banks (with amounts provided by Manuel, who was the Minister of Finance at the time):[7][21] The Arms Deal was subject to criticism on several different fronts.

Although the majority of the ensuing controversy centred on corruption allegations and concerns that fair procurement processes had not been followed (see below), the deal was also criticised from an early stage on grounds relating to its cost and underlying strategy.

The document from which she read became infamous as the "De Lille dossier," and contained allegations against Tony Yengeni, Schabir Shaik, Thabo Mbeki,[29] and Jacob Zuma, amongst others.

[30] Another Arms Deal activist, Terry Crawford-Browne, later alleged that the dossier had been compiled by ANC intelligence operatives working with whistleblowers inside the party, including Winnie Madikizela-Mandela.

"[44] It declined to publicly disclose findings "of a criminal and sensitive nature," but noted that the investigators had heard some allegations of corruption and conflict of interest which "appeared to have substance and are currently being pursued.

[45][46][47] In October 2011, President Jacob Zuma, Mbeki's successor, appointed a judicial commission of inquiry to investigate the Arms Deal, chaired by Willie Seriti and also including Willem van der Merwe and Francis Legodi.

[61][62] Ahead of the JCC hearings, Seriti and Musi submitted a court application to halt the process, challenging the constitutionality of the provision of the JSC Act which allows misconduct proceedings against retired judges, such as themselves.

[65] Although there have been very many public allegations about specific cases or relationships involving some such corruption, they have most frequently been limited to media reports – they have very rarely been corroborated by an official investigation or inquiry or tested in a criminal trial.

This allegedly occurred in 1998, while Yengeni chaired Parliament's joint standing committee on defence,[36] and a company in which EADS had a 33% stake ultimately won the contract to supply radar technology for the corvettes.

[78] The SFO found that BAE had paid £115 million (or R1.2 billion)[78] in commissions to several advisors (through at least eight different entities, primarily with offshore bank accounts)[79][44] to help secure the Arms Deal contracts.

[23] The Scorpions agreed that there was "at the very least a reasonable suspicion that Fana Hlongwane may have used some of the huge sums of money he received, either directly or through the various entities which he controlled, to induce and/or reward... assistance" of officials involved in the evaluation of the Arms Deal bids.

[78] A former regional managing director of BAE admitted to the SFO that Bredenkamp had been paid for his political connections, including his access to Chief of Acquisitions Chippy Shaik.

[42] It was also alleged that Aermacchi, an Italian bidder for the aircraft contracts, had been told that it had to subcontract a front company owned by associates of Modise in order to win the tender.

[88][76] In a 1998 fax leaked to the Times, the former regional head of BAE wrote:[T]he fact we have got Hawk on to the final list is very much due to our friends in the country rather than the quality of our ITP [invitation to prequalify] response.

[88]As mentioned above, Saab was contracted alongside BAE Systems to provide the fighter aircraft, and its South African subsidiary Sanip had signed consultancy agreements with Hlongwane.

[90] The announcement referred to "reciprocal agreements" by which Saab and two Swedish trade unions, including IF Metall, would support Numsa in establishing an industrial training school.

[98] About $22 million allegedly went through a company registered in Liberia to Tony Georgiadis, a Greek businessman, who was apparently hired by Thyssen as a lobbyist[99] and who had links to politicians including Mbeki and Bulelani Ngcuka.

[96] In November 2007, Patricia de Lille alleged in Parliament that in January 1999 Thyssen had paid R500,000 each to the ANC (through a Swiss bank account), to the Nelson Mandela Children's Fund, and to the Foundation for Community Development, a Mozambican charity linked to Graça Machel.

[102] In 2008, the Mail & Guardian reported that it had seen confidential documents showing that R500,000 payments had indeed been made in 1999 to the ANC, to the Nelson Mandela Children's Fund, and to the Foundation for Community Development, not directly from Thyssen but rather from Georgiadis.

[99] Der Spiegel alleged that internal memos appeared to show that Chippy Shaik had requested and received a $3-million payment from Thyssen as a fee for the success of its bid.

The memo records Shaik telling Thyssen representatives that the German Frigate Consortium's bidwas pulled into first place in spite of the Spanish offer being 20% cheaper.

[29] While Modise was Defence Minister, ThyssenKrupp subcontracted South African logistics coordinator Futuristic Business Solutions, at a price of R1.2 million, allegedly to influence procurement decisions.

[114] In January 2021, the Pietermaritzburg High Court declined to set aside the charges, finding that there was "reasonable and probable cause to believe" that Thales had been party to "a pattern of racketeering" with Shaik.

The court concluded that the annual payments were intended to purchase Zuma's assistance in protecting Thales from investigation and improving its profile for future government tenders.

[45] AmaBhungane reported that Shaik also appeared to have been involved in the local subsidiary which Ferrostaal set up in order to meet its close to €3-billion in offset obligations under the Arms Deal contract.