Cinema of South Korea

[5][6] The golden age of South Korean cinema in the mid-20th century produced what are considered two of the best South Korean films of all time, The Housemaid (1960) and Obaltan (1961),[7] while the industry's revival with the Korean New Wave from the late 1990s to the present produced both of the country's highest-grossing films, The Admiral: Roaring Currents (2014) and Extreme Job (2019), as well as prize winners on the festival circuit including Golden Lion recipient Pietà (2012) and Palme d'Or recipient and Academy Award winner Parasite (2019) and international cult classics including Oldboy (2003),[8] Snowpiercer (2013),[9] and Train to Busan (2016).

[12] With the surrender of Japan in 1945 and the subsequent liberation of Korea, freedom became the predominant theme in South Korean cinema in the late 1940s and early 1950s.

Additionally foreign aid arrived in the country after the war that provided South Korean filmmakers with equipment and technology to begin producing more films.

[15] Though filmmakers were still subject to government censorship, South Korea experienced a golden age of cinema, mostly consisting of melodramas, starting in the mid-1950s.

[16] One of the most popular films of the era, director Lee Kyu-hwan's now lost remake of Chunhyang-jeon (1955), drew 10 percent of Seoul's population to movie theaters[15] However, while Chunhyang-jeon re-told a traditional Korean story, another popular film of the era, Han Hyung-mo's Madame Freedom (1956), told a modern story about female sexuality and Western values.

[17] South Korean filmmakers enjoyed a brief freedom from censorship in the early 1960s, between the administrations of Syngman Rhee and Park Chung Hee.

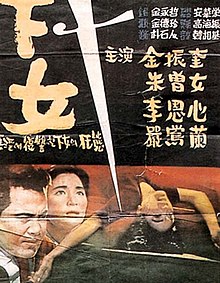

[18] Kim Ki-young's The Housemaid (1960) and Yu Hyun-mok's Obaltan (1960), now considered among the best South Korean films ever made, were produced during this time.

Under the Motion Picture Law of 1962, a series of increasingly restrictive measures was enacted that limited imported films under a quota system.

Notably, director Kim Soo-yong released ten films in 1967, including Mist, which is considered to be his greatest work.

[19] Government control of South Korea's film industry reached its height during the 1970s under President Park Chung Hee's authoritarian "Yusin System."

[26] The propaganda-laden movies (or "policy films") produced in the 1970s were unpopular with audiences who had become accustomed to seeing real-life social issues onscreen during the 1950s and 1960s.

In addition to government interference, South Korean filmmakers began losing their audience to television, and movie-theater attendance dropped by over 60 percent from 1969 to 1979.

[27] Films that were popular among audiences during this era include Yeong-ja's Heydays (1975) and Winter Woman (1977), both box office hits directed by Kim Ho-sun.

Censoring of scripts in pre-production was officially dismissed in the late 1980s, still producers were unofficially expected to present two copies to the Public Performance Ethics Committee,[31] who had the power to modify by completely cutting scenes.

However, they had already laid the groundwork for a renaissance in South Korean film-making by supporting young directors and introducing good business practices into the industry.

[39] South Korean films began attracting significant international attention in the 2000s, due in part to filmmaker Park Chan-wook, whose movie Oldboy (2003) won the Grand Prix at the 2004 Cannes Film Festival and was praised by American directors including Quentin Tarantino and Spike Lee, the latter of whom directed the remake Oldboy (2013).