Stanislaus River

Originally inhabited by the Miwok group of Native Americans, the Stanislaus River was explored in the early 1800s by the Spanish, who conscripted indigenous people to work in the colonial mission and presidio systems.

Water managers have struggled to find a balance between competing needs, which also include groundwater recharge, flood control, and river-based recreation such as fishing and whitewater rafting.

Stretching from the foothill to alpine regions of the Sierra Nevada, it consists of rugged narrow canyons and ridges with an average local relief of 2,000 feet (610 m) or more from river to rim.

[20] The Stanislaus River is believed to have originally formed sometime during the Miocene period, about 23 million years ago, flowing down from an ancient mountain range in the current location of the Sierra Nevada that has since eroded away.

About 9 million years ago during the Pliocene, the most recent period of orogeny (uplift) occurred, tilting the predominantly granitic Sierra Nevada batholith to form a regional slope to the west.

[27][28] As both uplift and erosion continued, the Stanislaus River gradually carved the rugged canyons it flows through today, and contributed to the vast alluvial deposits that make up the flat floor of the Central Valley.

[27] These glaciers carved large U-shaped valleys in the high elevations, and supplied vast volumes of meltwater which accelerated erosion along the foothill canyons of the Stanislaus River.

The Mexican army, led by Mariano Vallejo, moved to crush the resistance, but was initially defeated by natives on the Laquisimes River, in a place believed to be near present-day Caswell Memorial State Park.

[44] After the initial defeat, Vallejo returned with a force of "107 soldiers, some citizens, and at least fifty mission Indian militiamen" armed with muskets and cannon, but again fought to a draw.

The entire mining camp of Dry Diggings (near today's Placerville), about 200 men in all, packed up and headed south to the Stanislaus River, and as news spread throughout the Gold Country, hundreds more arrived.

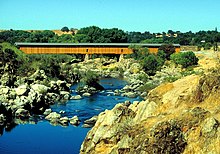

[57] In 1849 William Knight, a hunter and trapper, established a ferry and trading post on the Stanislaus River, to serve the thousands of miners headed to the diggings at Sonora and other mining camps.

[78] However, after the completion of New Melones Dam in 1979, and especially due to drought in recent years, federal and local agencies have often been forced to compromise in order to divide limited Stanislaus River supplies between the many demands.

Harrold in 1895, improved on this system, building 47 miles (76 km) of canals along the north side of the Stanislaus River and supplying water to some 3,000 acres (1,200 ha) in Manteca and Oakdale.

[83] The original Melones Dam, completed 1926, was a 211-foot (64 m) tall concrete arch structure capable of storing 112,500 acre-feet (0.1388 km3) of water, enough to irrigate 144,000 acres (58,000 ha) of land for a single season but too small to provide carry-over storage for drought years.

[94][98] The New Melones project is well known for a legal battle between environmentalists, the state of California and the federal government which began in the 1970s as recreational whitewater rafting exploded in popularity.

[102][103] As a result, the state of California under Governor Jerry Brown (who also objected to New Melones on economic grounds) issued a temporary limit in November 1980 to keep the lake level below Parrott's Ferry Bridge, which marked the lower end of the Stanislaus whitewater.

[105] The state and environmentalists agreed to compromise the lake level at 26 percent of its design capacity, which hydrological studies determined was the optimal volume for fulfilling demands along the Stanislaus without losing too much water to evaporation and flood releases.

[100][109] The floods demonstrated the value of the dam in preventing $50 million of property damage[110] and capturing a huge volume of water that would otherwise have flowed into the ocean, prompting the state of California to lift the temporary limit.

However, other projects were also built purely to take advantage of the river's great hydroelectric potential: in a span of about 60 miles (97 km), the Stanislaus descends almost 10,000 feet (3,000 m) from the headwaters of the Middle Fork to the valley floor at Knight's Ferry.

[119] Because the water is diverted so far upstream, it affords a head of over 1,000 feet (300 m) to the Stanislaus Powerhouse; the much heavier flow of the Middle Fork means that more power can be generated – about 91 megawatts at full capacity.

[117][120] PG&E also built the original 22 megawatt power station at the old 1926 Melones Dam, under a 40-year contract with the Oakdale and South San Joaquin Irrigation Districts.

[121] An added benefit was that the Donnells and Beardsley dams regulate water flow down the Middle Fork, allowing more consistent power generation at the older Stanislaus Powerhouse.

[120] During the spring snowmelt, these high-elevation hydro projects operate at full load around the clock; any river flow in excess of the powerhouse capacity must be spilled (bypassed) and becomes wasted energy.

[138] The Stanislaus River provides habitat for native anadromous fish, particularly Chinook (king) salmon, and steelhead, which spend their adult lives in the ocean but must return to fresh water to spawn.

[141] In 1992, federal dam operators began releasing large volumes of water or "pulse flows" into the Stanislaus River during the critical spring and fall spawning seasons hoping to replicate natural conditions of snowmelt and autumn storms, respectively, in order to help the fish reproduce.

[149][150] In 2017, the independent environmental consulting group FISHBIO released a study showing that the number of outmigrating fish may not be as strongly related to artificial pulse flows as previously thought.

[160] As of 2016, the Bureau of Reclamation is considering allowing commercial outfits to operate on the Camp Nine run once more, "whenever river flows and water levels in Melones Reservoir make it possible".

[165] Below Knights Ferry the Stanislaus becomes wider and smoother, with Class I-II rapids between there and Orange Blossom Park;[166] further downstream many parts of the river are suitable for flat-water boating and swimming.

Knight runs (14 miles (23 km) in total), rated "difficult" at Class IV–V+ are dependent on releases from Sand Bar Dam, which only occur when river flow exceeds the capacity of Stanislaus Powerhouse.

[183] Caswell Memorial State Park covers 258 acres (104 ha) along the lower Stanislaus River and is home to one of the last native riparian oak woodlands in the Central Valley.