Southern strategy

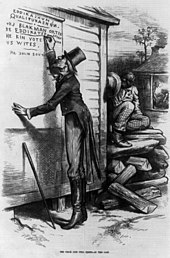

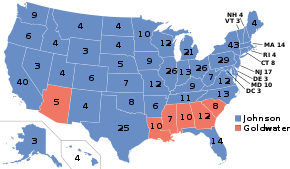

[1][2][3] As the civil rights movement and dismantling of Jim Crow laws in the 1950s and 1960s visibly deepened existing racial tensions in much of the Southern United States, Republican politicians such as presidential candidates Richard Nixon and Barry Goldwater developed strategies that successfully contributed to the political realignment of many white, conservative voters in the South who had traditionally supported the Democratic Party so consistently that the voting pattern was named the Solid South.

The scholarly consensus is that racial conservatism was critical in the post–Civil Rights Act realignment of the Republican and Democratic parties,[8][9] though several aspects of this view have been debated by historians and political scientists.

Gradually, Southern voters began to elect Republicans to Congress and finally to statewide and local offices, particularly as some legacy segregationist Democrats, such as Strom Thurmond, retired or switched to the GOP.

[20] During the 1876 United States presidential election, the Republican ticket of Rutherford B. Hayes and William A. Wheeler (later known as members of the comparably liberal "Half-Breed" faction) abandoned the party's pro-civil rights efforts of Reconstruction and made conciliatory tones to the South in the form of appeals to old Southern Whigs.

In the 1928 election, the Republican candidate Herbert Hoover rode the issues of prohibition and anti-Catholicism[33] to carry five former Confederate states, with 62 of the 126 electoral votes of the section.

Changes in industry and growth in universities and the military establishment in turn attracted Northern transplants to the South and bolstered the base of the Republican Party.

A Lyndon B. Johnson ad called "Confessions of a Republican", which ran in Northern and Western states, associated Goldwater with the Ku Klux Klan (KKK).

[87] The notion of Black Power advocated by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee leaders captured some of the frustrations of African Americans at the slow process of change in gaining civil rights and social justice.

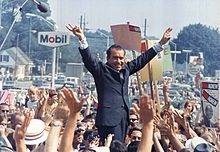

[90] With the aid of Harry Dent and South Carolina Senator Strom Thurmond, who had switched to the Republican Party in 1964, Nixon ran his 1968 campaign on states' rights and "law and order".

[93] Nixon met with southern Republicans and party chairmen, including John Tower and Thurmond, on May 31, 1968, in Atlanta, Georgia, and promised to slow integration efforts and forced busing.

At the local level, the 1970s saw steady Republican growth with this emphasis on a middle-class suburban electorate that had little interest in the historic issues of rural agrarianism and racial segregation.

Helms received large amounts of support from white voters and tied himself to Reagan and opposition to Martin Luther King Jr. Day during the 1984 election.

Bryce Harlow stated that Bush would have been better for party unity, but that Rockefeller would receive better coverage from the media and make Ford a stronger candidate in the 1976 election.

Lee Atwater and Carroll A. Campbell Jr. managed his successful campaign in South Carolina despite John Connally having the support of Thurmond and Governor James B. Edwards.

[139] In August 1980, Reagan made a much-noted appearance at the Neshoba County Fair in Philadelphia, Mississippi,[140] where his speech contained the phrase "I believe in states' rights".

[147][148] Dan Carter explains how "Reagan showed that he could use coded language with the best of them, lambasting welfare queens, busing, and affirmative action as the need arose".

[147][150] Aistrup described Reagan's campaign statements as "seemingly race neutral", but explained how whites interpret this in a racial manner, citing a Democratic National Committee funded study conducted by Communications Research Group.

[147] Aistrup argued that one example of Reagan field-testing coded language in the South was a reference to an unscrupulous man using food stamps as a "strapping young buck".

[156] Alabama, Florida, and Georgia designated the second Tuesday of March as the date for their presidential primaries and the Southern Legislative Conference lobbied other states to join.

[161] During the 1988 presidential election, the Willie Horton attack ads run against Democratic candidate Michael Dukakis built upon the Southern Strategy in a campaign that reinforced the notion that Republicans best represent conservative whites with traditional values.

[163] Upon seeing a favorable New Jersey focus group response to the Horton strategy, Atwater recognized that an implicit racial appeal could work outside of the Southern states.

[177][178] Black Baptists, on the other hand, served as a source of resistance to Jim Crow through parallel institutions, intellectual traditions, and activism which extend into the present day.

[187] In his article "The Race Problematic, the Narrative of Martin Luther King Jr., and the Election of Barack Obama", Dr. Rickey Hill argued that Bush implemented his own Southern Strategy by exploiting "the denigration of the liberal label to convince white conservatives to vote for him.

[192][193][194] Some historians believe that racial issues took a back seat to a grassroots narrative known as the "suburban strategy", which Glen Feldman calls a "dissenting—yet rapidly growing—narrative on the topic of southern partisan realignment".

[12] Matthew Lassiter says: "A suburban-centered vision reveals that demographic change played a more important role than racial demagoguery in the emergence of a two-party system in the American South".

[200] Bruce Kalk and George Tindall argue that Nixon's Southern Strategy was to find a compromise on race that would take the issue out of politics, allowing conservatives in the South to rally behind his grand plan to reorganize the national government.

Kalk says Nixon did end the reform impulse and sowed the seeds for the political rise of white Southerners and the decline of the civil rights movement.

Mayer states: Goldwater's staff also realized that his radical plan to sell the Tennessee Valley Authority was causing even racist whites to vote for Johnson.

Goldwater's opposition to most poverty programs, the TVA, aid to education, Social Security, the Rural Electrification Administration, and farm price supports surely cost him votes throughout the South and the nation.

A close examination of the evidence, however, reveals that in the area of school desegregation, Nixon's record was a mixture of principle and politics, progress and paralysis, success and failure.