Soviet–Canadian 1988 Polar Bridge Expedition

The Soviet–Canadian 1988 Polar Bridge Expedition (also known as Skitrek) began on March 3, 1988, when a group of thirteen Russian and Canadian skiers set out from Siberia, in an attempt to ski to Canada over the North Pole.

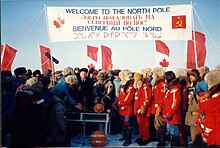

At the North Pole, they were welcomed by a group of dignitaries from the Soviet Union and Canada, members of the international press, and radio amateurs involved in support and communications.

In the autumn of 1986, a group of Soviet scientists and radio amateurs made plans to ski to the South Pole, starting at the Antarctic coast.

However, it is not a good idea to rely on radio propagation conditions to the other side of the world, even with a support station on the Antarctic continent itself; so, in November, 1986, the University of Surrey (UoS) UoSAT centre was contacted to investigate the feasibility of using the UoSAT-OSCAR-11 satellite to relay information to the skiers.

The Canadian and Russian skiers trained in both Canada and Siberia during the months prior to the expedition and also tried to learn to speak and understand each other's language.

[5][6] The Russian group consisted of:[7] expedition leader and Arctic explorer Dmitry Shparo; photographer Alexander (Sasha) Belyayev, also in charge of meals; artist Fyodor Konyukhev; cameraman Vladimir Ledenev; physician Mikhail (Misha) Malakhov; radio operators Anatoli Melnikov and Vasili Shishkaryov; Anatoly Fedyakov who was responsible for equipment; and researcher Yuri Hmelevsky.

The four Canadians were: navigator Richard Weber; radio operator Laurie Dexter; doctor Max Buxton; and scientist Chris Holloway.

Communications were handled via HF (shortwave) amateur radio between the skiers and support stations on and near the Arctic Ocean, and headquarters in Moscow and Ottawa.

The University of Surrey's orbiting space satellite UoSAT-OSCAR-11 was used to relay the position of the group, using the on-board Digitalker,[8] (a computer speech synthesizer).

At this time, before the advent of GPS, the position of the group was obtained by celestial measurements made by skiers themselves, and by using a beacon or Emergency Locator Transmitter (ELT) to send signals to be picked up by one of the COSPAS and SARSAT 'Search and Rescue' satellites when it flies overhead.

The position is calculated by command and tracking stations in Moscow and Canada, using the on-board stored date and time of the signal, and the measured Doppler effect, (a shift in frequency due to the relative velocity between the beacon and the satellite).

It weighed 1.2 kilograms without batteries and had six fixed, crystal controlled frequencies for single-sideband (SSB) operation on the 80, 40 and 20 meter amateur radio bands.

The 2 kg lithium battery provided the 2.2 amps at 12 V required to operate the transceiver for about a month, one hour per day, at low temperatures.

The support stations were manned and set up by amateur radio volunteers in remote areas, close to or on the Arctic Ocean at: One of the problems was composing, from a limited vocabulary, a proper DIGITALKER message for the expedition.

The daily routine consisted of a steady 10- to 12-hour trek, followed by setting up their single twelve-man tent, switching on their ELT, having a meal of dried food, and spending a few minutes on the shortwave radio (80 m).

Eleven parachute assisted drops were made in two passes over the skiers with an Antonov AN-74 Soviet plane, specially designed for this type of expedition work.

[14] All were flown in by helicopter from NP-28, the Soviet drifting ice station about 30 km from the North Pole, which contained an airstrip suitable for the Antonov AN-74, and Canadian Twin Otter and Hawker Siddeley HS748 airplanes.