Soviet art

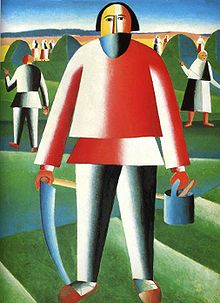

The Russian Revolution led to an artistic and cultural shift within Russia and the Soviet Union as a whole, including a new focus on socialist realism in officially approved art.

During the 1920s, there was intense ideological competition between different artistic groupings striving to determine the forms and directions in which Soviet art would develop, seeking to occupy key posts in cultural institutions and to win the favor and support of the authorities.

At the turn of the 1930s, many avant-garde tendencies had exhausted themselves, and their former proponents began depicting real-life objects as they attempted to return to the traditional system of painted images, including the leading Jack of Diamonds artists.

[2] A group of prominent supporters of leftist views included David Shterenberg, Alexander Drevin, Vladimir Tatlin, Wassily Kandinsky, Kazimir Malevich, Osip Brik, Sofya Dymshits-Tolstaya, Olga Rozanova, Mikhail Matyushin, and Nathan Altman.

The avant-garde movement attracted the interests of the Proletkult organization,[5] which was highly eclectic in its art forms and included modern directions like impressionism and cubism.

In the spring of 1932, the Central Committee of the Communist Party decreed that all existing literary and artistic groups and organizations should be disbanded and replaced with unified associations of creative professions.

[8] Among them were such major artists and sculptors of the USSR as Alexander Samokhvalov, Yevsey Moiseyenko, Andrei Mylnikov, Yuri Neprintsev, Aleksandr Laktionov, Mikhail Anikushin, Piotr Belousov, Boris Ugarov, Ilya Glazunov, Nikolai Timkov, and others.

Nikita Khrushchev later alleged that Kliment Voroshilov spent more time posing in Gerasimov's studio than he did attending to his duties in the People's Commissariat of Defense.

A great number of landscapes, portraits, genre paintings, and studies exhibited at the time pursued purely technical purposes and were thus free from any ideology.

That approach was also pursued ever more consistently in the genre paintings as well, although young artists at the time still lacked the experience and professional mastery to produce works of high art level devoted to Soviet actuality.

[10] A known Russian art historian, Vitaly Manin, considered that «what in our time is termed a myth in the works of artists of the 1930s was a reality, and one, moreover, that was perceived that way by real people.

Images of youths and students, rapidly changing villages and cities, virgin lands brought under cultivation, grandiose construction plans being realized in Siberia and the Volga region, and great achievements of Soviet science and technology became the chief topics of the new painting.

[citation needed] The death of Joseph Stalin in 1953 and Nikita Khrushchev's Thaw paved the way for a wave of liberalization in the arts throughout the Soviet Union.

Although no official change in policy took place, artists began to feel free to experiment in their work with considerably less fear of repercussions than during the Stalinist period.

The most important figures for the international art scene have been the Moscow artists Ilya Kabakov, Erik Bulatov, Andrei Monastyrsky, Vitaly Komar, and Aleksandr Melamid.

However, the foreign press had been there to witness the event, and the worldwide coverage of it forced the authorities to permit an exhibition of nonconformist art two weeks later in Izmailovsky Park in Moscow.

Kenda and Jacob Bar-Gera, both survivors of the Holocaust, supported these partially persecuted artists by sending them money or painting materials from Germany to the Soviet Union.

The works were smuggled to Germany by hiding them in the suitcases of diplomats, traveling businessmen, and students, thus making the Bar-Gera Collection of Russian Non-Conformists among the largest of its kind in the world.

By the end of the 1980s, Mikhail Gorbachev's policies of Perestroika and Glasnost made it virtually impossible for the authorities to place restrictions on artists or their freedom of expression.