Spacecraft cemetery

The area is roughly centered on "Point Nemo", the oceanic pole of inaccessibility, the location farthest from any land.

Other spacecraft that have been routinely scuttled in the region include various cargo spacecraft to the International Space Station, including Russian Progress cargo craft,[5] the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency H-II Transfer Vehicle,[6] and the European Space Agency's Automated Transfer Vehicle.

[11] Current considerations of the spacecraft cemetery include the environmental impact it creates on marine life within the South Pacific Ocean Uninhabited Region.

[1][11] This location has been chosen for its remoteness and limited shipping traffic so as not to endanger human life with any falling debris.

During an extended mission phase, control was lost due to a power failure, leading to an uncontrolled landing outside of the spacecraft cemetery.

International treaties exist but do not clearly assign responsibility to countries about the liability for damages and pollution caused by re-entering space debris.

[12] Among the pertinent regulations, two general agreements concerning space debris and marine pollution are often expanded upon to govern the spacecraft cemetery.

Hydrazine, a widely used rocket propellant that is highly toxic to living organisms, may occasionally survive re-entry.

[12] There are numerous domestic and international regulatory bodies intended to mitigate potential environmental damage caused by spacecraft pollution.

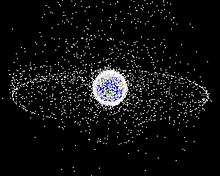

[12] Currently more than 27,000 pieces of space debris are orbiting earth at high velocities, threatening the safety of human and robotic missions, as well as causing damage to spacecraft.