Spacecraft thermal control

It must cope with the external environment, which can vary in a wide range as the spacecraft is exposed to the extreme coldness found in the shadows of deep space or to the intense heat found in the unfiltered direct sunlight of outer space.

Thermal control is also necessary to keep specific components (such as optical sensors, atomic clocks, etc.)

The thermal control subsystem can be composed of both passive and active items and works in two ways: Passive thermal control system (PTCS) components include: Active thermal control system (ATCS) components include: For a spacecraft the main environmental interactions are the energy coming from the Sun and the heat radiated to deep space.

The temperature requirements of the instruments and equipment on board are the main factors in the design of the thermal control system.

All of the electronic instruments on board the spacecraft, such as cameras, data-collection devices, batteries, etc., have a fixed operating temperature range.

Some examples of temperature ranges include Coatings are the simplest and least expensive of the TCS techniques.

A coating may be paint or a more sophisticated chemical applied to the surfaces of the spacecraft to lower or increase heat transfer.

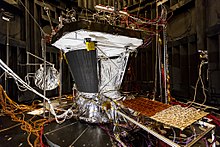

Multilayer insulation (MLI) is the most common passive thermal control element used on spacecraft.

The outer cover layer needs to be opaque to sunlight, generate a low amount of particulate contaminates, and be able to survive in the environment and temperature to which the spacecraft will be exposed.

Heaters are used in thermal control design to protect components under cold-case environmental conditions or to make up for heat that is not dissipated.

Most spacecraft radiators reject between 100 and 350 W of internally generated electronics waste heat per square meter.

The radiators of the International Space Station are clearly visible as arrays of white square panels attached to the main truss.