Spanish Baroque literature

[1] The fundamental characteristics of Spanish Baroque literature are the progressive complexity in formal resources and a theme centered on the concern for the passage of time and the loss of confidence in the Neoplatonic ideals of the Renaissance.

Likewise, the variety and diversity in the subjects dealt with, the attention to detail and the desire to attract a wide audience, of which the rise of the Lope de Vega comedies are an example.

From the dominant sensual concern in the 16th century, there was an emphasis on moral values and didactics, where two currents converge: Neostoicism and Neoepicureism.

El Criticón from Baltasar Gracián is a point of arrival in the baroque reflection on man and the world, the awareness of disappointment, a vital pessimism and a general crisis of values.

is characterized by the following features:[citation needed] In view of the crisis of the Baroque, Spanish writers reacted in several ways: The narrative of the 17th century opens with the figure of Miguel de Cervantes, who returned to Spain in 1580 after ten years absence.

It is a pastoral novel (see Spanish Renaissance literature) in six books of verse and prose, according to the model of the Diana of Montemayor; although it breaks with the tradition when introducing realistic elements, like the murder of a shepherd, or the agility of certain dialogues.

It relates, in four books, how Periandro and Auristela travel from northern territories of Norway or Finland to Rome to receive Christian marriage.

As is typical of this subgenre, throughout the trip they experience a variety of trials, mishaps, and delays: captivity by Barbarians, the jealousy and machinations of rivals.

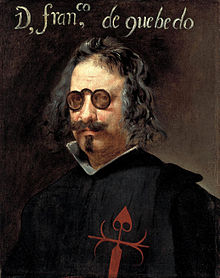

Francisco de Quevedo wrote towards 1604 his first work of prose fiction : the picaresque novel titled The Life Story of the Sharper called Don Pablos, example of wanderers and mirror of rogues.

Operating by antithesis Quevedo shows doctors who are in fact executioners, the rich as poor but thieving, and a whole gallery of social types, offices and states is presented, all implacably satirized.

Marcus Brutus (1644) arises from glosses or commentaries to the biography that Plutarch wrote on this Latin statesman in his Parallel lives.

Gracián cultivated didactic prose in treatises of moral intention and practical purpose, like The Hero (1637), The Politician don Fernando the Catholic (1640) or The Discreet one (1646).

The Manual oracle and art of prudence is a set of three hundred aphorisms composed to help the reader prevail in the complex world-in-crisis of the 17th century.

(An English version of this dense treatise has been sold as a manual of self-help for executives and has obtained a recent publishing success.)

He also wrote a rhetoric of Baroque literature, that starts from the texts to redefine the figures of speech of the time, because they did not relate to the classical models.

The world is seen as a hostile space full of deceit and illusion triumphing over virtue and truth, where Man is a self-interested and malicious being.

Gracián is recognized as precursor of existentialism, he also influenced French moralists like La Rochefoucauld, and, in the 19th century, the philosophy of Schopenhauer.

Góngora's lyric collection consists of numerous sonnets, odes, ballads, songs for guitar, and of certain larger poems, such as the Soledades and the Polifemo, the two landmarks of culteranismo.

The function began with a performance on guitar of a popular piece; immediately, songs accompanied with diverse instruments were sung.

The poet wrote the comedy, paid by the director, to whom he yielded all the rights on the work, represented or printed, to modify the text.

His most famous work is Life is a dream (1635), a philosophical drama in which Segismundo, son of the king of Poland, is chained in a tower because of the fateful predictions of the royal astrologers that he will kill his father.