Spanish conquest of the Maya

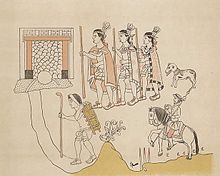

Maya warriors fought with flint-tipped spears, bows and arrows, stones, and wooden swords with inset obsidian blades, and wore padded cotton armour to protect themselves.

[28] At the time of conquest, polities in the northern Yucatán peninsula included Mani, Cehpech, and Chakan;[25] further east along the north coast were Ah Kin Chel, Cupul, and Chikinchel.

[36] In the centuries preceding the arrival of the Spanish the Kʼicheʼ had carved out a small empire covering a large part of the western Guatemalan Highlands and the neighbouring Pacific coastal plain.

[nb 1] The conquistadors were all volunteers, the majority of whom did not receive a fixed salary but instead a portion of the spoils of victory, in the form of precious metals, land grants and provision of native labour.

[57] Native resistance to the new nucleated settlements took the form of the flight of the indigenous inhabitants into inaccessible regions such as the forest or joining neighbouring Maya groups that had not yet submitted to the Spanish.

[56] Horses had never been encountered by the Maya before,[62] and their use gave the mounted conquistador an overwhelming advantage over his unmounted opponent, allowing the rider to strike with greater force while simultaneously making him less vulnerable to attack.

[75] The Spanish described the weapons of war of the Petén Maya as bows and arrows, fire-sharpened poles, flint-headed spears and two-handed swords crafted from strong wood with the blade fashioned from inset obsidian,[76] similar to the Aztec macuahuitl.

[67] In response to the use of cavalry, the highland Maya took to digging pits on the roads, lining them with fire-hardened stakes and camouflaging them with grass and weeds, a tactic that according to the Kaqchikel killed many horses.

[103] The ship's pilot then steered a course for Cuba via Florida, and Hernández de Cordóba wrote a report to Governor Diego Velázquez describing the voyage and, most importantly, the discovery of gold.

[117] In 1522 Cortés sent Mexican allies to scout the Soconusco region of lowland Chiapas, where they met new delegations from Iximche and Qʼumarkaj at Tuxpán;[118] both of the powerful highland Maya kingdoms declared their loyalty to the King of Spain.

[124] In 1524,[113] after the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, Hernán Cortés led an expedition to Honduras over land, cutting across Acalan in southern Campeche and the Itza kingdom in what is now the northern Petén Department of Guatemala.

[128] Cortés found a village on the shore of Lake Izabal, and crossed the Dulce River to the settlement of Nito, somewhere on the Amatique Bay,[131] with about a dozen companions, and waited there for the rest of his army to regroup over the next week.

The Spanish founded a new town at nearby Tecpán Guatemala, abandoned it in 1527 because of continuous Kaqchikel attacks, and moved to the Almolonga Valley to the east, refounding their capital at Ciudad Vieja.

[185] Alvarado sent 40 men to cover the exit from the cave and launched another assault along the ravine, in single file owing to its narrowness, with crossbowmen alternating with musketmen, each with a companion sheltering him with a shield.

[191] The richer lands of Mexico engaged the main attention of the Conquistadors for some years, then in 1526 Francisco de Montejo (a veteran of the Grijalva and Cortés expeditions)[192] successfully petitioned the King of Spain for the right to conquer Yucatán.

Late in 1528, Montejo left d'Avila to oversee Xamanha and sailed north to loop around the Yucatán Peninsula and head for the Spanish colony of New Spain in central Mexico.

[161] The Province of Chiapa had no coastal territory, and at the end of this process about 100 Spanish settlers were concentrated in the remote provincial capital at Villa Real, surrounded by hostile Indian settlements, and with deep internal divisions.

In August 1528, Mazariegos replaced the existing encomenderos with his friends and allies; the natives, seeing the Spanish isolated and witnessing the hostility between the original and newly arrived settlers, took this opportunity to rebel and refused to supply their new masters.

[161] The Mazariegos family managed to establish a power base in the local colonial institutions and, in 1535, they succeeded in having San Cristóbal de los Llanos declared a city, with the new name of Ciudad Real.

Montejo the Younger abandoned Ciudad Real by night, and he and his men fled west, where the Chel, Pech, and Xiu provinces remained obedient to Spanish rule.

[237] On 29 January 1686, Captain Melchor Rodríguez Mazariegos, acting under orders from the governor, left Huehuetenango for San Mateo Ixtatán, where he recruited indigenous warriors from the nearby villages.

[238] To prevent news of the Spanish advance reaching the inhabitants of the Lacandon area, the governor ordered the capture of three of San Mateo's community leaders, and had them sent under guard to be imprisoned in Huehuetenango.

[241] In 1695 the colonial authorities decided to act upon a plan to connect the province of Guatemala with Yucatán,[242] and a three-way invasion of the Lacandon was launched simultaneously from San Mateo Ixtatán, Cobán and Ocosingo.

[256] Dominican friar Bartolomé de las Casas arrived in the colony of Guatemala in 1537 and immediately campaigned to replace violent military conquest with peaceful missionary work.

[258] one could make a whole book ... out of the atrocities, barbarities, murders, clearances, ravages and other foul injustices perpetrated ... by those that went to Guatemala In this way they congregated a group of Christian Indians in the location of what is now the town of Rabinal.

[271] The friars returned in October 1619, and again Kan Ekʼ welcomed them in a friendly manner, but this time the Maya priesthood were hostile and the missionaries were expelled without food or water, but survived the journey back to Mérida.

[272] In the 1640s internal strife in Spain distracted the government from attempts to conquer unknown lands; the Spanish Crown lacked the time, money or interest in such colonial adventures for the next four decades.

[281] At the beginning of March 1695, Captain Alonso García de Paredes led a group of 50 Spanish soldiers south into Kejache territory, accompanied by native guides, muleteers and labourers.

[289] García ordered the construction of a fort at Chuntuki, some 25 leagues (approximately 65 miles or 105 km) north of Lake Petén Itzá, which served as the main military base for the Camino Real ("Royal Road") project.

[322] During the campaign to conquer the Itza of Petén, the Spanish sent expeditions to harass and relocate the Mopan north of Lake Izabal and the Chʼol Maya of the Amatique forests to the east.