Sparta

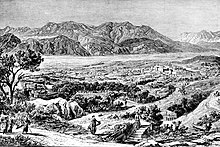

In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (Λακεδαίμων, Lakedaímōn), while the name Sparta referred to its main settlement in the valley of Evrotas river in Laconia, in southeastern Peloponnese.

However, Sparta was sacked in 396 AD by the Visigothic king Alaric, and underwent a long period of decline, especially in the Middle Ages, when many of its citizens moved to Mystras.

The reality enabled the Spartans to defeat Athens in war; the myth influenced Plato's political theory, and that of countless subsequent writers.... [The] ideals that it favors had a great part in framing the doctrines of Rousseau, Nietzsche, and National Socialism.

The third term, "Laconice" (Λακωνική), referred to the immediate area around the town of Sparta, the plateau east of the Taygetos mountains,[8] and sometimes to all the regions under direct Spartan control, including Messenia.

[17] In Homer it is typically combined with epithets of the countryside: wide, lovely, shining and most often hollow and broken (full of ravines),[18] suggesting the Eurotas Valley.

[24][25][26][27] Thucydides wrote: Suppose the city of Sparta to be deserted, and nothing left but the temples and the ground-plan, distant ages would be very unwilling to believe that the power of the Lacedaemonians was at all equal to their fame.

Their city is not built continuously, and has no splendid temples or other edifices; it rather resembles a group of villages, like the ancient towns of Hellas, and would therefore make a poor show.

The votive offerings in clay, amber, bronze, ivory and lead dating from the 9th to the 4th centuries BC, which were found in great profusion within the precinct range, supply invaluable information about early Spartan art.

Though the actual temple is almost completely destroyed, the site has produced the longest extant archaic inscription in Laconia, numerous bronze nails and plates, and a considerable number of votive offerings.

[31][better source needed] Excavations made from the early 1990s to the present suggest that the area around the Menelaion in the southern part of the Eurotas valley seems to have been the center of Mycenaean Laconia.

Its area was approximately equal to that of the "newer" Sparta, but denudation has wreaked havoc with its buildings and nothing is left of its original structures save for ruined foundations and broken potsherds.

[37] Several writers throughout antiquity, including Herodotus, Xenophon, and Plutarch have attempted to explain Spartan exceptionalism as a result of the so-called Lycurgan Reforms.Xenophon, Constitution of the Lacedaimonians, chapter 1[38][39][40] In the Second Messenian War, Sparta established itself as a local power in the Peloponnesus and the rest of Greece.

Even though this war was won by a pan-Greek army, credit was given to Sparta, who besides providing the leading forces at Thermopylae and Plataea, had been the de facto leader of the entire Greek expedition.

In the course of the Peloponnesian War, Sparta, a traditional land power, acquired a navy which managed to overpower the previously dominant flotilla of Athens, ending the Athenian Empire.

At the peak of its power in the early 4th century BC, Sparta had subdued many of the main Greek states and even invaded the Persian provinces in Anatolia (modern day Turkey), a period known as the Spartan hegemony.

[50] After a few more years of fighting, in 387 BC the Peace of Antalcidas was established, according to which all Greek cities of Ionia would return to Persian control, and Persia's Asian border would be free of the Spartan threat.

Spartan political independence was put to an end when it was eventually forced into the Achaean League after its defeat in the decisive Laconian War by a coalition of other Greek city-states and Rome, and the resultant overthrow of its final king Nabis, in 192 BC.

The state was ruled by two hereditary kings of the Agiad and Eurypontid families,[75] both supposedly descendants of Heracles and equal in authority, so that one could not act against the power and political enactments of his colleague.

[95] What made Sparta's relations with her slave population unique was that the helots, precisely because they enjoyed privileges such as family and property, retained their identity as a conquered people (the Messenians) and also had effective kinship groups that could be used to organize rebellion.

For they ordained that each one of them must wear a dogskin cap (κυνῆ / kunễ) and wrap himself in skins (διφθέρα / diphthéra) and receive a stipulated number of beatings every year regardless of any wrongdoing, so that they would never forget they were slaves.

[108] Though the conspicuous display of wealth appears to have been discouraged, this did not preclude the production of very fine decorated bronze, ivory and wooden works of art as well as exquisite jewellery, attested in archaeology.

[111] However, from early on there were marked differences of wealth within the state, and these became more serious after the law of Epitadeus some time after the Peloponnesian War, which removed the legal prohibition on the gift or bequest of land.

[115] Sparta is often viewed as being unique in this regard, however, anthropologist Laila Williamson notes: "Infanticide has been practiced on every continent and by people on every level of cultural complexity, from hunter gatherers to high civilizations.

According to some sources, the older man was expected to function as a kind of substitute father and role model to his junior partner; however, others believe it was reasonably certain that they had sexual relations (the exact nature of Spartan pederasty is not entirely clear).

Thus, the shield was symbolic of the individual soldier's subordination to his unit, his integral part in its success, and his solemn responsibility to his comrades in arms – messmates and friends, often close blood relations.

[138]One of the most persistent myths about Sparta that has no basis in fact is the notion that Spartan mothers were without feelings toward their off-spring and helped enforce a militaristic lifestyle on their sons and husbands.

One of them decidedly supports the need to disguise the bride as a man in order to help the bridegroom consummate the marriage, so unaccustomed were men to women's looks at the time of their first intercourse.

The reasons for delaying marriage were to ensure the birth of healthy children, but the effect was to spare Spartan women the hazards and lasting health damage associated with pregnancy among adolescents.

The philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau contrasted Sparta favourably with Athens in his Discourse on the Arts and Sciences, arguing that its austere constitution was preferable to the more sophisticated Athenian life.

Tabenkin, a founding father of the Kibbutz movement and the Palmach strikeforce, prescribed that education for warfare "should begin from the nursery", that children should from kindergarten be taken to "spend nights in the mountains and valleys".