Spatial anti-aliasing

In digital signal processing, spatial anti-aliasing is a technique for minimizing the distortion artifacts (aliasing) when representing a high-resolution image at a lower resolution.

Anti-aliasing means removing signal components that have a higher frequency than is able to be properly resolved by the recording (or sampling) device.

When sampling is performed without removing this part of the signal, it causes undesirable artifacts such as black-and-white noise.

In computer graphics, anti-aliasing improves the appearance of "jagged" polygon edges, or "jaggies", so they are smoothed out on the screen.

In contrast, when anti-aliased the checker-board near the top blends into grey, which is usually the desired effect when the resolution is insufficient to show the detail.

Particularly with fonts displayed on typical LCD screens, it is common to use subpixel rendering techniques like ClearType.

Equivalent results can be had by making individual sub-pixels addressable as if they were full pixels, and supplying a hardware-based anti-aliasing filter as is done in the OLPC XO-1 laptop's display controller.

Otherwise, the brightness of each pixel will be equal to the darkest value calculated in time for that location which produces a very bad result.

For more sophisticated shapes, the algorithm may be generalized as rendering the shape to a pixel grid with higher resolution than the target display surface (usually a multiple that is a power of 2 to reduce distortion), then using bicubic interpolation to determine the average intensity of each real pixel on the display surface.

The goal of an anti-aliasing filter is to greatly reduce frequencies above a certain limit, known as the Nyquist frequency, so that the signal will be accurately represented by its samples, or nearly so, in accordance with the sampling theorem; there are many different choices of detailed algorithm, with different filter transfer functions.

The filter usually considered optimal is not rotationally symmetrical, as shown in this first figure; this is because the data is sampled on a square lattice, not using a continuous image.

As an example, when printing a photographic negative with plentiful processing capability and on a printer with a hexagonal pattern, there is no reason to use sinc function interpolation.

When rendering the image, the appropriate-resolution mipmap is chosen and hence the texture pixels (texels) are already filtered when they arrive on the screen.

Mipmapping is generally combined with various forms of texture filtering in order to improve the final result.

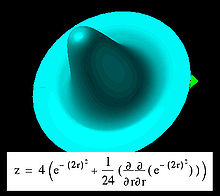

Because fractals have unlimited detail and no noise other than arithmetic round-off error, they illustrate aliasing more clearly than do photographs or other measured data.

To show what was discarded, the rejected points, blended into a grey background, are shown in the fourth image.

But due to its tremendous computational cost and the advent of multisample anti-aliasing (MSAA) support on GPUs, it is no longer widely used in real time applications.

Rendering at larger resolutions will produce better results; however, more processor power is needed, which can degrade performance and frame rate.

Sometimes FSAA is implemented in hardware in such a way that a graphical application is unaware the images are being super-sampled and then down-sampled before being displayed.

These anti-aliasing primitives are joined to the silhouetted edges, and create a region in the image where the objects appear to blend into the background.

[5] Using linear arithmetic on a gamma-compressed image results in values which are slightly different from the ideal filter.

This error is larger when dealing with high contrast areas, causing high contrast areas to become dimmer: bright details (such as a cat's whiskers) become visually thinner, and dark details (such as tree branches) become thicker, relative to the optically anti-aliased image.