Spevack v. Klein

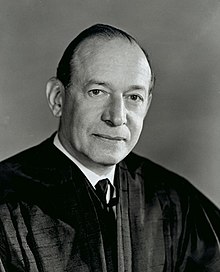

It was a very close case, being 5–4, with the majority only winning with the vote of Justice Abe Fortas who wrote a special concurring opinion on the matter.

[1] Around 1965, attorney Samuel Spevack of the New York State Bar Association was under investigation and was served with a subpoena to produce various financial and business documents.

[2] Solomon A. Klein throughout these proceedings was the named respondent, this was due to him having been the Chief Counsel to the Judiciary Inquiry on Professional Conduct of the New York State Supreme Court.

[5] Its decision had rested on Cohen and that, "the Fifth Amendment privilege does not apply to a demand, not for oral testimony, but that an attorney produce records required by law to be kept by him" (citing Davis v. United States, 328 U.S. 582 and Shapiro v. United States, 335 U.S. 1).Judge Stanley H. Fuld, who went on to become the Chief Judge of the New York Court of Appeals in 1967, wrote a concurring memorandum in which he expressed disdain in this case, showing he disagreed with Cohen decision but was bound by it.

In Hogan, it was reinforced that no person should be punished for their silence by virtue of their Fifth Amendment right, protected and incorporated by the Fourteenth, and the majority determined that the threat of disbarment and its eventual execution was a violation of that precedent.

"They further argue that this decision would be devastating to the legal profession in the public eye, since attorneys and would-be applicants can claim Fifth Amendment protection to shield themselves from any proper investigation.

This is put together by saying, "[This case] exposes this Court itself to the possible indignity that it may one day have to admit to its own bar such a lawyer unless it can somehow get at the truth of suspicions, the investigation of which the applicant has previously succeeded in blocking.

"They further reason that even with the Hogan decision, the Court need not be so hasty in completely overturning Cohen, and further that the plurality didn't have deep enough thought or consideration at the "true issue", that being,"whether petitioner's disbarment for his failure to provide information relevant to charges of misconduct in carrying on his law practice impermissibly vitiated the protection afforded by the privilege.

They argue that this case doesn't satisfy either prerequisite, and further continue to speak on the fact that States, through their bar associations, are given a large amount of leeway in what they can require for their professions.

Finally, a State may, without constitutional objection, require in the same fashion continuing evidence of professional and moral fitness as a condition of the retention of the right to practice.

The scathing article was written largely from the perspective of someone involved greatly from within a bar association, mainly talking about how public perception of the legal profession would fall following the ruling.

He wrote, "If, as the Court has held, the furnishing of an attorney is an essential part of the administration of justice for which the state is responsible, it would seem to follow that the state is at least as interested in the integrity of the attorneys it licenses as in the integrity of its employees" There has however been some opinions to show that the ruling wasn't completely wrong, with specifically one article arguing that Spevack doesn't wish to regard a bar disciplinary hearing as criminal, which is generally the only context in which the Fifth Amendment may be invoked.