Spherical tokamak

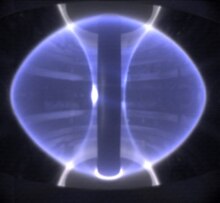

A traditional tokamak has a toroidal confinement area that gives it an overall shape similar to a donut, complete with a large hole in the middle.

Major experiments in the ST field include the pioneering START and MAST at Culham in the UK, the US's NSTX-U and Russian Globus-M. Research has investigated whether spherical tokamaks are a route to lower cost reactors.

[1] The simplest way to do this is to heat the fuel to very high temperatures, and allow the Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution to produce a number of very high-energy atoms within a larger, cooler mix.

Tokamaks confine their fuel at low pressure (around 1/millionth of atmospheric) but high temperatures (150 million Celsius), and attempt to keep those conditions stable for ever-increasing times on the order of seconds to minutes.

This has led to a variety of machines that operate at ever higher temperatures and attempt to maintain the resulting plasma in a stable state long enough to meet the desired triple product.

However, it is also essential to maximize the η for practical reasons, and in the case of a MFE reactor, that generally means increasing the efficiency of the confinement system, notably the energy used in the magnets.

[4][5] Improving beta means that you need to use, in relative terms, less energy to generate the magnetic fields for any given plasma pressure (or density).

During the 1980s, researchers at Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL), led by Ben Carreras and Tim Hender, were studying the operations of tokamaks as A was reduced.

[7] In the traditional tokamak design, the confinement magnets are normally arranged outside a toroidal vacuum chamber holding the plasma.

[9] The downside to this approach, one that was widely criticized in the field, is that it places the magnets directly in the high-energy neutron flux of the fusion reactions.

[11] In 1984,[12] Martin Peng of ORNL proposed an alternate arrangement of the magnet coils that would greatly reduce the aspect ratio while avoiding the erosion issues of the compact tokamak.

What was once a series of individual rings passing through the hole in the center of the reactor was reduced to a single post, allowing for aspect ratios as low as 1.2.

[5][13] This means that STs can reach the same operational triple product numbers as conventional designs using one tenth the magnetic field.

If you consider a D on the right side and a reversed D on the left, as the two approach each other (as A is reduced) eventually the vertical surfaces touch and the resulting shape is a circle.

A number of experimental spheromak machines were built in the 1970s and early 80s, but demonstrated performance that simply was not interesting enough to suggest further development.

Built at Heidelberg University in the early 1980s, HSE was quickly converted to a ST in 1987 by adjusting its magnetic coils at the outside of the confinement area and attaching them to a new central conductor.

Peng's advocacy also caught the interest of Derek Robinson, of the United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority (UKAEA) fusion center at Culham.

Robinson assembled a team and secure funding on the order of 100,000 pounds to build an experimental machine, the Small Tight Aspect Ratio Tokamak, or START.

[20] Parts of the machine were recycled from earlier projects, while others were loaned from other labs, including a 40 keV neutral beam injector from ORNL.

A practical rule of thumb in conventional designs is that as the operational beta approaches a value normalized for the machine size, ballooning instability destabilizes the plasma.

[23]START demonstrated Peng and Strickler's predictions; ST had performance an order of magnitude better than conventional designs, and cost much less to build.

Meanwhile START found new life as part of the revolutionary Proto-Sphera project in Italy, where experimenters attempted to eliminate the central column by passing the current through a secondary plasma.

One set of magnets is logically wired in a series of rings around the outside of the tube, but are physically connected through a common conductor in the center.

The central column is also normally used to house the solenoid that forms the inductive loop for the ohmic heating system (and pinch current).

Advances in plasma physics in the 1970s and 80s led to a much stronger understanding of stability issues, and this developed into a series of "scaling laws" that can be used to quickly determine rough operational numbers across a wide variety of systems.

to be 1.5/5 = 0.24, then: So in spite of the higher beta in the ST, the overall power density is lower, largely due to the use of superconducting magnets in the traditional design.

This issue has led to considerable work to see if these scaling laws hold for the ST, and efforts to increase the allowable field strength through a variety of methods.

In 1954 Edward Teller hosted a meeting exploring some of these issues, and noted that he felt plasmas would be inherently more stable if they were following convex lines of magnetic force, rather than concave.

However, in a normal high-A design, q varies only slightly as the particle moves about, as the relative distance from inside the outside is small compared to the radius of the machine as a whole (the definition of aspect ratio).

[35] Luckily, high elongation and triangularity are the features that give rise to these currents, so it is possible that the ST will actually be more economical in this regard.