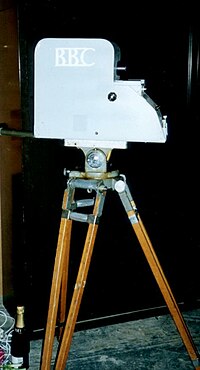

405-line television system

It was introduced with the BBC Television Service in 1936, suspended for the duration of World War II, and remained in operation in the UK until 1985.

Sometimes called the Marconi-EMI system, it was developed in 1934 by the EMI Research Team led by Isaac Shoenberg.

In the United States, the FCC had briefly approved a 405-line color television standard in October 1950, which was developed by CBS.

The committee recommended that a "high definition" service (defined by them as being a system of 240 lines or more) should be run and established by the BBC.

The BBC temporarily ceased transmissions on 1 September 1939, the day of the German invasion of Poland, for the outbreak of World War II was imminent.

After the BBC Television Service recommenced in 1946, distant reception reports were received from various parts of the world, including Italy, South Africa, India, the Middle East, North America and the Caribbean.

The BBC lost its monopoly of the British television market in 1954, and the following year the commercial network ITV, comprising a consortium of regional companies, was launched.

Ireland's use of the 405-line system began in 1961 (officially 31st of December 1961), with the launch of Telefís Éireann, but only extended to two main transmitters and their five relays, serving the east and north of the country.

Colour was provided mechanically by means of a synchronized rotating transparent Red-Green-Blue disk, which was placed in front of the receiver screen.

Regular broadcast channels were used to transmit the 405-line system signals, but the millions of existing NTSC 525-line television receivers could only correctly process the audio portion of these transmissions, so unless these sets were modified they would only display a jumbled picture.

CBS's efforts were hindered from the beginning by a widespread lack of acceptance, and the ultimate setback came at the end of the year when the U.S. government temporarily banned the manufacture of colour televisions, ostensibly to conserve resources during the Korean War.

Secondly, the smoothing (filtering) of power supply circuits in early TV receivers was rather poor, and ripple superimposed on the DC could cause visual interference.

However, the main problem was the susceptibility of the electron beam in the CRT being deflected by stray magnetic fields from nearby transformers or motors.

An interlaced system requires accurate positioning of scanning lines so the horizontal and vertical timebase must be in a precise ratio.

The technology constraints of the 1930s meant that this division process could only be done using small integers, preferably no greater than 7, for good stability.

This preserves the original 50-field interlaced format, but with some geometrical distortions owing to the curvature of the CRT monitors used at the time.

The use of AM (rather than FM) for sound and the use of positive (rather than negative) video modulation made 405-line signals very prone to audible and visible impulse interference, such as that generated by the ignition systems of vehicles.

With positive modulation, interference could easily be of similar amplitude to the sync pulses (which were represented by 0–30% of the transmitter output).

As a result, impulse interference would cause visual dark spots before it was large enough to affect the synchronisation of the picture.

The later introduction of flywheel sync circuits rendered the picture much more stable, but these could not have alleviated some of the problems with positive modulation.

Thus for a completely black picture, the AGC circuit would increase the RF gain to restore the average carrier amplitude.

In fact, the total light output of early TV sets was practically constant regardless of the picture content.

The introduction of negative modulation in later systems simplified the problem because peak carrier power represented sync pulses (which were always guaranteed to be present).

A simple peak-detector AGC circuit would detect the amplitude of only the sync pulses, thus measuring the strength of the received signal.

Modern sets using plasma, LCD or OLED display technology are completely free of this effect as they are composed of a million or more individually controllable elements, rather than using a single magnetically deflected beam, so there is no requirement to generate the scanning signal.