Chinook salmon

According to NOAA, the Chinook salmon population along the California coast is declining from factors such as overfishing, loss of freshwater and estuarine habitat, hydropower development, poor ocean conditions, and hatchery practices.

[8] In certain areas such as California's Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta, it was revealed that extremely low numbers of juvenile Chinook salmon (less than 1%) were surviving.

[9] In the western Pacific, the distribution ranges from northern Japan (Hokkaido) in the south to the Arctic Ocean as far as the East Siberian Sea and Palyavaam River in the north.

Also, in parts of the northern Magadan Oblast near the Shelikhov Gulf and Penzhina Bay, stocks might persist but remain poorly studied.

[12] Chinook salmon have been found spawning in headwater reaches of the Rio Santa Cruz, apparently having migrated over 1,000 km (620 mi) from the ocean.

[13] Sporadic efforts to introduce the fish to New Zealand waters in the late 19th century were largely failures and led to no evident establishments.

The Chinook is blue-green, red, or purple on the back and on the top of the head, with silvery sides and white ventral surfaces.

The commercial catch world record is 57 kg (126 lb) caught near Rivers Inlet, British Columbia, in the late 1970s.

Salmon lose the silvery blue they had as ocean fish, and their color darkens, sometimes with a radical change in hue.

These fish travel over 2,100 m (7,000 ft) in elevation, and over 1,400 km (900 mi), in their migration through eight dams and reservoirs on the Columbia and Lower Snake Rivers.

Riparian vegetation and woody debris help juvenile salmon by providing cover and maintaining low water temperatures.

They rely on eelgrass and seaweeds for camouflage (protection from predators), shelter, and foraging habitat as they make their way to the open ocean.

With some populations endangered, precautions are necessary to prevent overfishing and habitat destruction, including appropriate management of hydroelectric and irrigation projects.

[7] In the Pacific Northwest, the summer runs of especially large Chinook once common (before dams and overfishing led to declines) were known as June hogs.

The bone can record the chemical composition of the water the fish had lived in, just as a tree's growth rings provide hints about dry and wet years.

Japan is New Zealand's largest export market, with stock also being supplied to other countries of the Pacific Rim, including Australia.

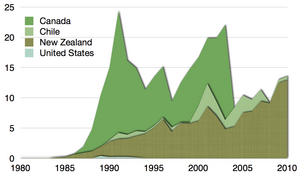

[30] Farming of the species in New Zealand began in the 1970s when hatcheries were initially set up to enhance and support wild fish stocks, with the first commercial operations starting in 1976.

[14] After some opposition against their establishment by societal groups, including anglers, the first sea cage farm was established in 1983 at Big Glory Bay in Stewart Island by British Petroleum NZ Ltd.[14][30] Today, the salmon are hatched in land-based hatcheries (several of which exist) and transferred to sea cages or freshwater farms, where they are grown out to the harvestable size of 3–4 kilograms (7–9 pounds).

After hatching, the baby salmon are typically grown to the smolt stage (around six months of age) before they are transferred to the sea cages or ponds.

In recognition of the sustainable, environmentally conscious practices, the New Zealand salmon farming industry has been acknowledged as the world's greenest by the Global Aquaculture Performance Index.

[34] The fall and late-fall runs in the Central Valley population in California is a U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) species of concern.

[35] In April 2008, commercial fisheries in both Oregon and California were closed in response to the low count of Chinook salmon present because of the collapse of the Sacramento River run, one of the biggest south of the Columbia.

[38] Scientists from universities and federal, state, and tribal agencies concluded the 2004 and 2005 broods were harmed by poor ocean conditions in 2005 and 2006, in addition to "a long-term, steady degradation of the freshwater and estuarine environment."

[44] In addition to dam removal, KRRC is also conducting efforts to revegetate certain areas in the watershed with trees and native grasses.

[45] As of December 2022, the plan is in its monitoring phase, in which ODFW are studying 10,000 hatchery-born spring-run Chinook released in certain tributaries of Upper Klamath Lake.

[47] A 2016 survey of Wisconsin anglers found they would, on average, pay $140 for a trip to catch Chinook salmon, $90 for lake trout, and $180 for walleye.

While salmon fishing in general remains important economically for many tribal communities, it is especially the Chinook harvest that is typically the most valuable.

Maritime fur traders and explorers, such as George Vancouver, frequently acquired salmon by trade with the indigenous people of the Northwest coast.

[57] It has been known that the creation of dams has negatively impacted the lives of many Native American Indians by disrupting their food supply and the flow of water.

[58] Representatives of the Shasta Indian Nation claimed that the construction of Copco No 1 Dam caused the submerging of sites significant to them, including burial grounds.