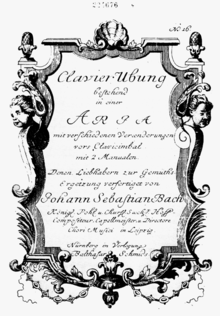

Aria

: ariette; in English simply air) is a self-contained piece for one voice, with or without instrumental or orchestral accompaniment, normally part of a larger work.

The Italian term aria, which derives from the Greek ἀήρ and Latin aer (air), first appeared in relation to music in the 14th century when it simply signified a manner or style of singing or playing.

By the early 16th century it was in common use as meaning a simple setting of strophic poetry; melodic madrigals, free of complex polyphony, were known as madrigale arioso.

In such works, the sung, melodic, and structured aria differed from the speech-like (parlando) recitative – the latter tending to carry the story-line, the former used to convey emotional content and serve as an opportunity for singers to display their vocal talent.

[4] Da capo aria with ritornelli became a typifying feature of European opera throughout the 18th century and is thought by some writers to be a direct antecedent of sonata form.

[5] The ritornelli became essential to the structure of the aria – "while the words determine the character of a melody the ritornello instruments often decided in what terms it shall be presented.

"[6] By the early 18th century, composers such as Alessandro Scarlatti had established the aria form, and especially its da capo version with ritornelli, as the key element of opera seria.

M. F. Robinson describes the standard aria in opera seria in the period 1720 to 1760 as follows: The first section normally began with an orchestral ritornello after which the singer entered and sang the words of the first stanza in their entirety.

As in opera buffa, the singers were often masters of the stage and the music, decorating the vocal lines so floridly that audiences could no longer recognise the original melody.

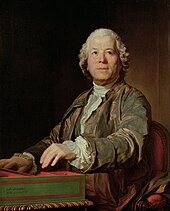

Gluck wanted to return opera to its origins, focusing on human drama and passions and making words and music of equal importance.

The effects of these Gluckist reforms were seen not only in his own operas but in the later works of Mozart; the arias now become far more expressive of the individual emotions of the characters and are both more firmly anchored in, and advance, the storyline.

Richard Wagner was to praise Gluck's innovations in his 1850 essay "Opera and Drama": " The musical composer revolted against the wilfulness of the singer"; rather than "unfold[ing] the purely sensuous contents of the Aria to their highest, rankest, pitch", Gluck sought "to put shackles on Caprice's execution of that Aria, by himself endeavouring to give the tune [...] an expression answering to the underlying Word-text".