Squaw

[8] The term squaw is considered offensive by Indigenous peoples in America and Canada due to its use for hundreds of years in a derogatory context[3] that demeans Native American women.

[5] Seneca Nation President Maurice John Sr., and Chief G. Ava Hill of the Six Nations of the Grand River wrote letters petitioning for the name change as well, with Chief Hill writing, The continued use and acceptance of the word 'Squaw' only perpetuates the idea that indigenous women and culture can be deemed as impure, sexually perverse, barbaric and dirty ...

[19] A will written in the Massachusett language by a native preacher from Martha's Vineyard uses the word squa to refer to his unmarried daughters.

[19] Records accompanying sketches by Alfred Jacob Miller document mid-19th century usage of the term in the United States.

For "Bourgeois" Walker, & his Squaw, Miller describes his depiction of the fur trader made in 1858 thusly: "The sketch exhibits a certain etiquette.

[Walker] had the kindness to present the writer a dozen pair of moccasins worked by this squaw - richly embroidered on the instep with colored porcupine quills.

[25] Colville / Okanagan author Mourning Dove, in her 1927 novel, Cogewea, the Half-Blood had one of her characters say, If I was to marry a white man and he would dare call me a 'squaw'—as an epithet with the sarcasm that we know so well—I believe that I would feel like killing him.[26]E.

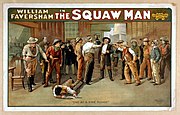

White's 1961 story "The Years of Wonder", derived from his 1923 journal of a shipboard trip to Alaska, included, "Mr. Hubbard ... saw that Siberia was represented by a couple of dozen furry Eskimos and one squaw man; they came aboard from a skin boat as soon as the Buford dropped her hook.

[28] LaDonna Harris, a Comanche social activist who spoke about empowering Native American schoolchildren in the 1960s at Ponca City, Oklahoma, recounted: We tried to find out what the children found painful about school [causing a very high dropout rate].

[30] An early comment in which squaw appears to have a sexual meaning is from the Canadian writer E. Pauline Johnson, who was of Mohawk heritage, but spent little time in that culture as an adult.

[19] In November 2021, the U.S. Department of the Interior declared squaw to be a derogatory term and began formally removing the term from use on the federal level, with Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland (Laguna Pueblo) announcing the creation of a committee and process to review and replace derogatory names of geographic features.

Our nation’s lands and waters should be places to celebrate the outdoors and our shared cultural heritage – not to perpetuate the legacies of oppression.

Today’s actions will accelerate an important process to reconcile derogatory place names and mark a significant step in honoring the ancestors who have stewarded our lands since time immemorial.