Squid

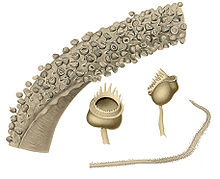

The pen, made of a chitin-like material,[5][6] is a feather-shaped internal structure that supports the squid's mantle and serves as a site for muscle attachment.

A set of eight arms and two distinctive tentacles surround the mouth; each appendage takes the form of a muscular hydrostat and is flexible and prehensile, usually bearing disc-like suckers.

These features, as well as strong musculature, and a small ganglion beneath each sucker to allow individual control, provide a very powerful adhesion to grip prey.

[15][16] Such skin camouflage may serve various functions, such as communication with nearby squid, prey detection, navigation, and orientation during hunting or seeking shelter.

[15] Neural control of the iridophores enabling rapid changes in skin iridescence appears to be regulated by a cholinergic process affecting reflectin proteins.

Giant axons up to 1 mm (0.04 in) in diameter convey nerve messages with great rapidity to the circular muscles of the mantle wall, allowing a synchronous, powerful contraction and maximum speed in the jet propulsion system.

[5] In shallow-water species of the continental shelf and epipelagic or mesopelagic zones, it is frequently one or both of arm pair IV of males that are modified into hectocotyli.

[25] Giant squid of the genus Architeuthis are unusual in that they possess both a large penis and modified arm tips, although whether the latter are used for spermatophore transfer is uncertain.

The mouth is equipped with a sharp, horny beak mainly made of chitin and cross-linked proteins,[27] which is used to kill and tear prey into manageable pieces.

[5] In some species, toxic saliva helps to control large prey; when subdued, the food can be torn in pieces by the beak, moved to the oesophagus by the radula, and swallowed.

The digestive gland, which is equivalent to a vertebrate liver, diverticulates here, as does the pancreas, and both of these empty into the caecum, a pouch-shaped sac where most of the absorption of nutrients takes place.

[33] Unlike nautiloids and cuttlefish which have gas-filled chambers inside their shells which provide buoyancy, and octopuses which live near and rest on the seabed and do not require to be buoyant, many squid have a fluid-filled receptacle, equivalent to the swim bladder of a fish, in the coelom or connective tissue.

This reservoir acts as a chemical buoyancy chamber, with the heavy metallic cations typical of seawater replaced by low molecular-weight ammonium ions, a product of excretion.

Glass squids in the family Cranchiidae for example, have an enormous transparent coelom containing ammonium ions and occupying about two-thirds the volume of the animal, allowing it to float at the required depth.

[35] The smallest species are probably the benthic pygmy squids Idiosepius, which grow to a mantle length of 10 to 18 mm (0.4 to 0.7 in), and have short bodies and stubby arms.

[39] In February 2007, a New Zealand fishing vessel caught the largest squid ever documented, weighing 495 kg (1,091 lb) and measuring around 10 m (33 ft) off the coast of Antarctica.

Once the bacteria enter the squid, they colonize interior epithelial cells in the light organ, living in crypts with complex microvilli protrusions.

Bioluminescence reaches its highest levels during the early evening hours and bottoms out before dawn; this occurs because at the end of each day, the contents of the squid's crypts are expelled into the surrounding environment.

During this means of locomotion, some squid exit the water in a similar way to flying fish, gliding through the air for up to 50 m (160 ft), and occasionally ending up on the decks of ships.

Prey is identified by sight or by touch, grabbed by the tentacles which can be shot out with great rapidity, brought back to within reach of the arms, and held by the hooks and suckers on their surface.

[5] The deep sea squid Taningia danae has been filmed releasing blinding flashes of light from large photophores on its arms to illuminate and disorientate potential prey.

[44] Although squid can catch large prey, the mouth is relatively small, and the food must be cut into pieces by the chitinous beak with its powerful muscles before being swallowed.

[5] The deep sea squid Mastigoteuthis has the whole length of its whip-like tentacles covered with tiny suckers; it probably catches small organisms in the same way that flypaper traps flies.

The Caribbean reef squid (Sepioteuthis sepioidea), for example, employs a complex array of colour changes during courtship and social interactions and has a range of about 16 body patterns in its repertoire.

[49] As well as occupying a key role in the food chain, squid are an important prey for predators including sharks, sea birds, seals and whales.

[55][56] The Gorgon of Greek mythology may have been inspired by squid or octopus, the animal itself representing the severed head of Medusa, the beak as the protruding tongue and fangs, and its tentacles as the snakes.

[58] Squid form a major food resource and are used in cuisines around the world, notably in Japan where it is eaten as ika sōmen, sliced into vermicelli-like strips; as sashimi; and as tempura.

[60] Three species of Loligo are used in large quantities: L. vulgaris in the Mediterranean (known as Calamar in Spanish, Calamaro in Italian); L. forbesii in the Northeast Atlantic; and L. pealei on the American East Coast.

[60] Among the Ommastrephidae, Todarodes pacificus is the main commercial species, harvested in large quantities across the North Pacific in Canada, Japan and China.

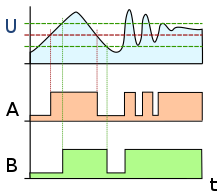

Prototype chromatophores that mimic the squid's adaptive camouflage have been made by Bristol University researchers using an electroactive dielectric elastomer, a flexible "smart" material that changes its colour and texture in response to electrical signals.