Basil of Caesarea

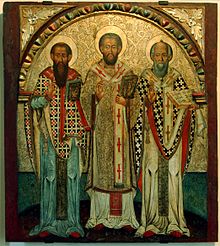

Semi-Autonomous: Basil of Caesarea, also called Saint Basil the Great (Koinē Greek: Ἅγιος Βασίλειος ὁ Μέγας, Hágios Basíleios ho Mégas; Coptic: Ⲡⲓⲁⲅⲓⲟⲥ Ⲃⲁⲥⲓⲗⲓⲟⲥ, Piagios Basílios; 330 – 1 or 2 January 379),[8] was an early Roman Christian prelate who served as Bishop of Caesarea in Cappadocia from 370 until his death in 379.

He was an influential theologian who supported the Nicene Creed and opposed the heresies of the early Christian church, fighting against both Arianism and the followers of Apollinaris of Laodicea.

In a letter, he described his spiritual awakening: I had wasted much time on follies and spent nearly all of my youth in vain labours, and devotion to the teachings of a wisdom that God had made foolish.

[25] Basil distributed his fortunes among the poor and went briefly into solitude near Neocaesarea of Pontus (modern Niksar), on the Iris River.

[25] Basil instead felt drawn toward communal religious life, and by 358 he was gathering around him a group of like-minded disciples, including his brother Peter.

Together they founded a monastic settlement on his family's estate near Annesi[24] (modern Sonusa or Uluköy, near the confluence of the Iris and Lycos rivers[27]).

[32] The Homoiousians opposed the Arianism of Eunomius but refused to join with the supporters of the Nicene Creed, who professed that the members of the Trinity were of one substance ("homoousios").

[32] His ability to balance his theological convictions with his political connections made Basil a powerful advocate for the Nicene position.

[23] Basil and Gregory Nazianzus spent the next few years combatting the Arian heresy, which threatened to divide Cappadocia's Christians.

They also show him encouraging his clergy not to be tempted by wealth or the comparatively easy life of a priest and taking care in selecting worthy candidates for holy orders.

In addition to all the above, he built a large complex just outside Caesarea, called the Basiliad,[36] which included a poorhouse, hospice, and hospital.

[37] His zeal for orthodoxy did not blind him to what was good in an opponent; and for the sake of peace and charity, he was content to waive the use of orthodox terminology when it could be surrendered without a sacrifice of truth.

This belief system, which denied that Christ was consubstantial with the Father, was quickly gaining adherents and was seen by many, particularly those in Alexandria most familiar with it, as posing a threat to the unity of the church.

Although Basil advocated objectively the consubstantiality of the Holy Spirit with the Father and the Son, he belonged to those, who, faithful to Eastern tradition, would not allow the predicate homoousios to the former; for this he was reproached as early as 371 by the Orthodox zealots among the monks, and Athanasius defended him.

[41] The great institute before the gates of Caesarea, the Ptochoptopheion, or "Basileiad", which was used as poorhouse, hospital, and hospice became a lasting monument of Basil's episcopal care for the poor.

Basil's writings and sermons, specifically on the topics of money and possessions, continue to influence modern Christianity.

[42] The principal theological writings of Basil are his On the Holy Spirit, an appeal to Scripture and early Christian tradition to prove the divinity of the Holy Spirit, and his Refutation of the Apology of the Impious Eunomius, which was written about in 364 and comprised three books against Eunomius of Cyzicus, the chief exponent of Anomoian Arianism.

[43] He was a famous preacher, and many of his homilies, including a series of Lenten lectures on the Hexaemeron (also Hexaëmeros, "Six Days of Creation"; Latin: Hexameron), and an exposition of the psalter, have been preserved.

On the other hand, Basil vehemently opposed the view that hell has an end in his short Regulae, even claiming that the many people who hold it are deceived by the devil.

Likewise, in Homilies on Psalms 1, PG 29.216–17, he insists on the Socratic and Stoic tenet, here Christianized, that man and woman have 'one and the same virtue' and 'one and the same nature' (φύσις).

This principle countered Aristotle's conviction and was consistent with Gregory of Nyssa's view and with that of many other patristic thinkers; even Augustine and Theodoret conceded this.

They show his observant nature, which, despite the troubles of ill-health and ecclesiastical unrest, remained optimistic, tender and even playful.

[52] Most of his extant works, and a few spuriously attributed to him, are available in the Patrologia Graeca, which includes Latin translations of varying quality.

Patristic scholars conclude that the Liturgy of Saint Basil "bears, unmistakably, the personal hand, pen, mind and heart of St.

The difference between the two is primarily in the silent prayers said by the priest, and in the use of the hymn to the Theotokos, All of Creation, instead of the Axion Estin of John Chrysostom's Liturgy.

[citation needed] Through his examples and teachings, Basil effected a noteworthy moderation in the austere practices which were previously characteristic of monastic life.

[60] Basil's teachings on monasticism, as encoded in works such as his Small Asketikon, were transmitted to the West via Rufinus during the late 4th century.

It is traditional on St Basil's Day to serve vasilopita, a rich bread baked with a coin inside.

Basil, who when a bishop, wanted to distribute money to the poor and commissioned some women to bake sweetened bread, in which he arranged to place gold coins.

[64] It is customary on his feast day to visit the homes of friends and relatives, to sing New Year's carols, and to set an extra place at the table for Saint Basil.