St. Croix macaw

A second specimen consisting of various bones from a similar site on Puerto Rico was described in 2008, while a coracoid from Montserrat may belong to this or another extinct species of macaw.

Macaws were frequently transported long distances by humans in prehistoric and historical times, so it is impossible to know whether species known only from bones or accounts were native or imported.

In 1934, the archeologist Lewis J. Korn (working under the Museum of the American Indian) excavated a kitchen midden (a dump for domestic waste) at a site near Concordia on the southwestern coast of St. Croix, one of the Virgin Islands in the Caribbean Sea.

The exact age of the material could not be determined, but since no European origin objects were found in the deposit, it was assumed to be pre-Columbian, between 500 and 800 years old.

[7] In 1987, the ornithologist Edgar J. Máiz López found several associated bones of a single bird (cataloged as USNM 44834) at the Hernández Colón archeological site on the eastern bank of the Cerrillos-Bucaná river in south central Puerto Rico.

They also pointed out that various animal species were transported and kept in captivity by Native Americans – for example the Puerto Rican hutia (Isolobodon portoricensis, an extinct rodent) and the Antillean cave rail (Nesotrochis debooyi, an extinct flightless rail) were both transported to St. Croix and found in kitchen middens.

[3] The ornithologists James W. Wiley and Guy M. Kirwan instead suggested in 2013 that the bone from Montserrat could belong to the extinct Lesser Antillean macaw (A. guadeloupensis) of Guadeloupe.

[7][9][10] The ornithologist Joseph M. Forshaw argued in 2017 that the latter was a more appropriate name since he found it more plausible that it naturally occurred on Puerto Rico and had been transported to the Virgin Islands.

Parrots were important in the culture of native Caribbeans and were among the gifts offered to the explorer Christopher Columbus when he reached the Bahamas in 1492.

[3] The identity and distribution of indigenous macaws in the Caribbean are likely to be resolved only through paleontological discoveries and examination of contemporary reports and artwork.

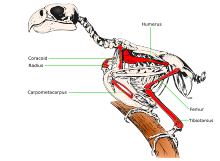

[10] While the holotype tibiotarsus appears to belong to a fully grown individual, the fact that the bone is slightly spongy at the ends indicates it was immature.

Compared to the tibiotarsi of extant macaws, the bone is more slender and has a slightly greater hindwards development of the upper end.

[3] Olson and Máiz López stated that extant macaws fall into two size-clusters, representing large and small species.

[3] Olson and Máiz López ruled out the specimen from Puerto Rico belonging to the Amazon parrots by pointing out characters found only in Ara macaws.

The femur has a proportionally larger head, and the tibiotarsus has a narrower internal condyle and a distinctive inner cnemial crest that is more pointed and extends further upwards.

[3] All the endemic Caribbean macaws were likely driven to extinction by humans (in prehistoric and historical times), though hurricanes and disease may have contributed.